The previous articles have proven popular:

Language Learning in Britain Past

Eng. Lit. in Britain Past

Music, Art & Divinity in Britain Past

So on to my two best subjects at school. I got a grade A in A level in each. No A * in those days. I felt sorry for my kids when ‘Humanities’ combined history, geography, music and art.

Bournemouth School is a state grammar school and moved its premises to East Way in 1939, just in time for the war. It shared its premises with King Edward VI school in Southampton during the war, so that Benny Hill was an ex-pupil. When Bournemouth School For Girls moved next door in my second year, it became known as Bournemouth School For Boys (BSB). Older masters were infuriated and insisted on deleting ‘For Boys.’

Each end of the main building had a larger classroom. Room 1 was at the far end, you can see it protruding. The library was above it. That was the Geography Room, larger to accommodate maps and a projector. At the other end, the near end, just out of view was Room 8, the History Room. Why it needed a larger classroom, I have no idea. But my two best subjects got bigger rooms.

Geography

Geography Grade A is shared by my daughter who has inherited my directional ability. My sons never did geography A level. One took 150 miles for a 75 mile journey (he got lost thinking Exeter was on the way from Bristol to Bournemouth). The other assured us that the way to a riverside restaurant was ‘up the hill’ because he was looking at google maps. No, you always go downhill to a river. Why would that be?

Both boys were at school in the 90s era when Geography became an option, and was barely taught. It’s had a comeback, mainly because the environment and climate change are again considered more crucial than (e.g) woodwork (just go to IKEA) or textile technology, aka needlework (just go to Primark). Judging by my grandkids the most important part is vulcanology (which has nothing to do with Mr Spock) as all geography homework seems to be about volcanoes and tectonic plates. There is more. Geography embraces meteorology, climate, physical geography, geology, political geography, economic geography, agricultural zones, town planning, map reading and orientation, oceanography. It is important.

So geography teaching. Not much good at my grammar school until the Sixth Form, when we had both deputy heads, Mr Barraclough for physical geography, Mr Dixon for economic. I don’t remember much about them, but both knew their subjects, were erudite, and the power of their deputy head positions meant that they could relax with us. There was no question of indiscipline. Dixon had a wry sense of humour.

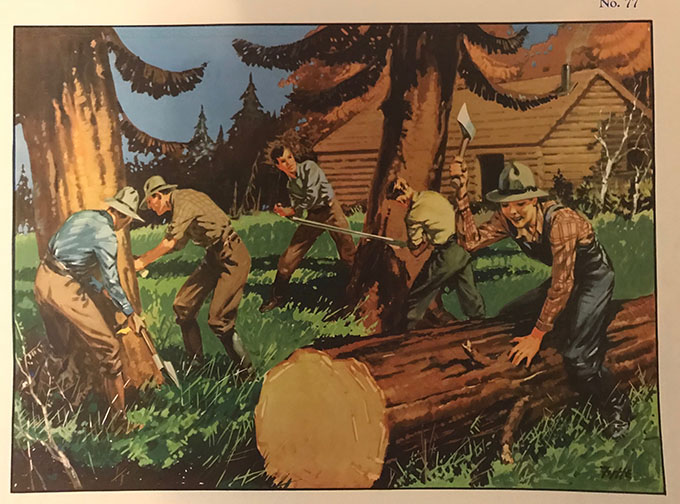

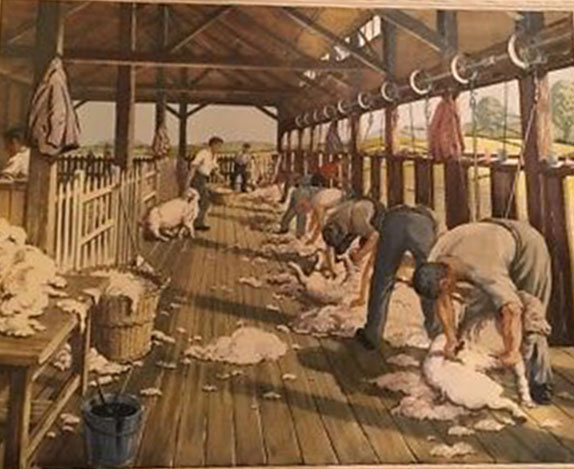

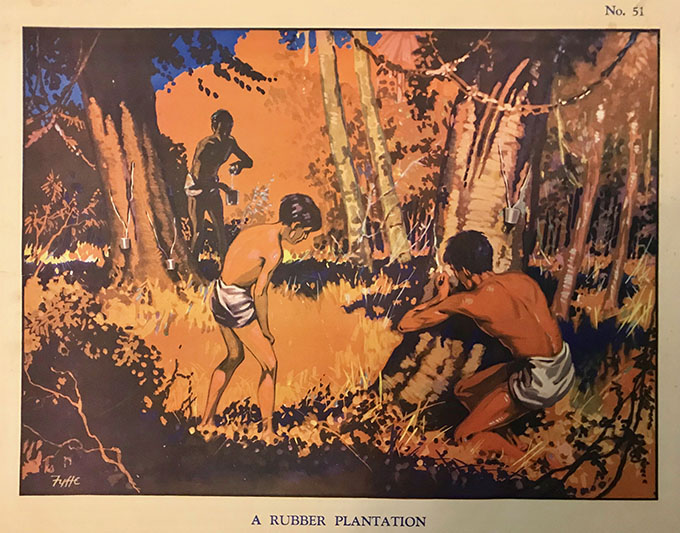

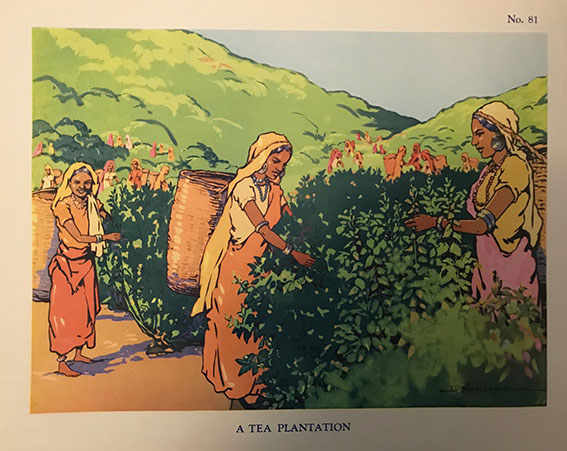

See below on history. We were still on the edge of the declining British Empire, then Commonwealth. The world had been arranged for our economic benefit. See the rant elsewhere POST-BREXIT VISION. These are extracted from it, and they are the posters used for classroom teaching at the time.

Canada was there for our timber and wheat. Australia existed for our wool. New Zealand for lamb and butter. Malaya brought us rubber for our tyres and Durex condoms. Ceylon brought our PG Tips and Typhoo. The Caribbean brought us sugar. The Gold Coast brought us cocoa, though irritatingly changed its name to Ghana and made the posters look out of date. South Africa provided us with sherry.

My problem in the early years was Mr Styles. Mr Styles had a system. All maps could be reduced to geometric shapes added together. Mr Styles refused to allow any other mapping. He believed these could be drawn fast in exams and were enough to add relevant information, like a dot for London or a circle for coalfields. I loved looking at maps. I loved drawing maps. I always used colours and carefully shaded pale blue around the outside of carefully drawn coastlines. He forbade that. I thought he was wrong, and still do.

Then we did Navigation in the enforced CCF RAF section. I got a distinction. That helped A levels considerably. Lucky it wasn’t 1940-1945. I’d have found myself strapped in a Lancaster bomber trying to read the map.

I could spend ages looking at historical atlases and that helped my history too. I don’t think it was the teaching though. At primary school I was told to improve my handwriting and I did it by writing lists from the geography section of Newnes Pictorial Knowledge: Uruguay – Montevideo, Chile- Santiago / Mount Everest. Mount Kilimanjaro etc.

In the third year we had a young, very nervous geography teacher, a Mr Swinfen, who couldn’t keep discipline so was “pinned against the board” in every lesson. I liked him, thought him informative, and felt very sorry for him. He’d lose discipline then freak out and start screaming uncontrollably at kids. You never let it get so far that you get that angry at farting noises when you turn to the blackboard. My old writing partner Bernie started teaching at a secondary school in Liverpool. His counsel was ‘Never try to be friends with kids at the start. Begin like Hitler with a bad headache, then when they know they can’t mess around. Relax the pressure. Then you can end up being a friend.’

Mr Swinfen went off sick with nervous exhaustion. The Woodwork teacher was made to teach us geography by reading from the book. His name was Ray Cutler, known as ‘Reg’ by the boys. That wasn’t his name, but Bournemouth and Boscombe Athletic FC (as it was then called) had a winger called Reg Cutler. In a fourth round FA Cup game against Wolverhampton Wanderers, he went to head the ball, headed the goalpost instead and broke it in half. It took half an hour to replace the goal, after which Reg Cutler shook his head a couple of times and continued playing and Bournemouth won 1-0. Reg, who broke the woodwork, was an appropriate name for a woodwork teacher with a thick head.

So our Reg spent his days screaming at us that it was ‘timber’ rather than ‘wood’, and throwing pieces at our heads and throwing them hard too. He was known for his constant questioning, ‘Was you talking, boy? Was you? What was you saying?’ Even we knew his grammar was lacking. So, his first geography lesson was the chapter on New York. It puzzled him. He kept muttering, ‘See, New York’s a state as well,’ as if it were news. He ended by looking at the next chapter heading, and saying ‘Next lesson is the next state, the state of New England.’ Always the smart arse, I raised my hand, ‘New England isn’t a state. It’s a collection of states, sir.’ He hit me. Yes, it was illegal. We were used to it. The next lesson he came in and said ‘We are going to look at the states of New England’ I sniggered. I got a detention.

That was not my last encounter with him. When my son was eleven we attended parent evenings at three prospective secondary schools. At one he stood on the stage. He was the deputy head (it was a secondary modern). On both sides were large menu boards for the school canteen. I counted seven spelling mistakes on display. As we went out, he said, ‘You was looking at me. Was you at Bournemouth School?’ I swallowed the temptation to say ‘Were you … Were you at Bournemouth School,’ and simply said, ‘Yes. Good to see you again, Mr Cutler.’

I think you have to do that. I loathed our headmaster. Twenty plus years after I left I was in the queue for Marks and Spencer’s checkout. I suddenly realised he had appeared behind me. He had a white stick. I automatically said, ‘Good morning, sir.’

He started, ‘Sir? So you must be a Bournemouth School old boy.’

‘Yes, er, sir.’

He asked my name and apologised that he could barely see me.

‘What are you doing now, Mr Viney?’

I said I was writing textbooks for Oxford University Press. He expressed great surprise, but smiled and said, ‘Of course I’m a Cambridge man, so you are in a sense a disappointment.’

We stood for five minutes while he told me proudly about his sons … one was in my year. We shook hands.

I told two friends that evening. One, whom he had expelled, said ‘I’d have taken the bastard’s white stick and run away with it!’ He was joking. (I think).

History

Our school had six intake forms in our baby boom year. About 180 of us. In some subjects they marked out of the whole year and ranked you. I fluctuated around the fourth class out of six – they were graded. Yet in history, I was always in the top five or six boys out of 180. OK, I was closer the other end in maths and science. I am not a polymath. Once I was second. The one who was first was said to be by far the brightest in the year. He went to Oxford and was allegedly expelled for trying to sell drugs to a police officer. So not that bright.

Our 1939 school had huge windows to the street and more to the corridor so that the headmaster could see what was going on as he patrolled the corridors, academic gown billowing behind him like Count Dracula. I spent a year staring at The Death of General Wolfe as I had a desk by the corridor window and it was right opposite. History lined the walls of the corridors, and the reproductions are more likely to have been chosen by the history department than the art department.

I spent another year staring at The Boyhood of Raleigh. I had a Raleigh bike too. And I now know the preferred spelling is Ralegh.

Did we have the next one? It wasn’t opposite any of my classrooms and yet it seems most familiar and they would have been remiss to exclude it. This was the heart of 1950s to 1960s history teaching. How Raleigh defeated the Spaniards (and brought tobacco to civilisation). How Sir Francis Drake singed the King of Spain’s beard. How Wolfe defeated Montcalm at the Plains of Abraham and secured Canada from the dastardly French. How Clive won India and pushed the French away. Horatio Nelson and the Battle of Trafalgar where he gloriously beat the French AND the Spanish. A double! Dr Livingstone opened up Africa. Captain Cook, The Pilgrim Fathers, George Washington … like Churchill’s histories, the English Speaking Peoples were embraced. Columbus and Magellan were European so slightly less interesting.

Nowadays this is all regarded as imperialistic and jingoistic. It used to be thought that Great Men (and they were men, except for Elizabeth I) were the key to history.

We studied Britain, America and Europe. Thirty years earlier at public schools, we wouldn’t have ventured much beyond Greece and Rome. It has turned the other way. My kids did The Babylonians, the Egyptians, the Aztecs and the Incas in a desperate effort to embrace other cultures. I don’t think this a good thing. Understanding present reality is aided by studying European history. learning about the World Wars, learning about the spread of the franchise, the emancipation of women. I remember my kids having stuff on the Dahomey woodcarvings and Great Zimbabwe. Isn’t it a bit patronizing? Don’t black kids think, ‘OK, but the Benin carvings are not Michelangelo’s David and the ruins of Zimbabwe are not Notre Dame cathedral, are they?’ Wouldn’t it be more useful to study the colonization of Africa by Europeans, and the way borders were created and the ensuing problems?

Then the ‘Great Men’ focus has continued, but now it’s ‘Great Person’ and vastly over-weighted on Mary Seacole. All my grandkids can tell me about Mary Seacole. She was lost to history for one hundred years. Inspiring? Possibly she was. A symbol? I see that. Historically important? Not in the slightest. Don’t search for black females who changed British history and force them into the curriculum, but explain why they didn’t change history.

Then we get the teaching of guilt for slavery. When I did my research MA in American Studies I was focussing on literature, but I had to earn a credit in history. I earned it by compiling lists from the microfiches at the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. I can assure the reader that the vast majority of African slaves were first captured by Africans (as they had been for centuries), sold to Arab traders who transported them to the European forts on the coast. Everyone bears the guilt. I had a discussion, or argument, with a Nigerian who thought Britain owed Nigeria some kind of compensation. Then he boasted that he was descended from chiefs. I said that in that case, his ancestors certainly had the blood of slave trading on their hands. Mine from rural Dorset and Pembrokeshire certainly did not.

So to my education.

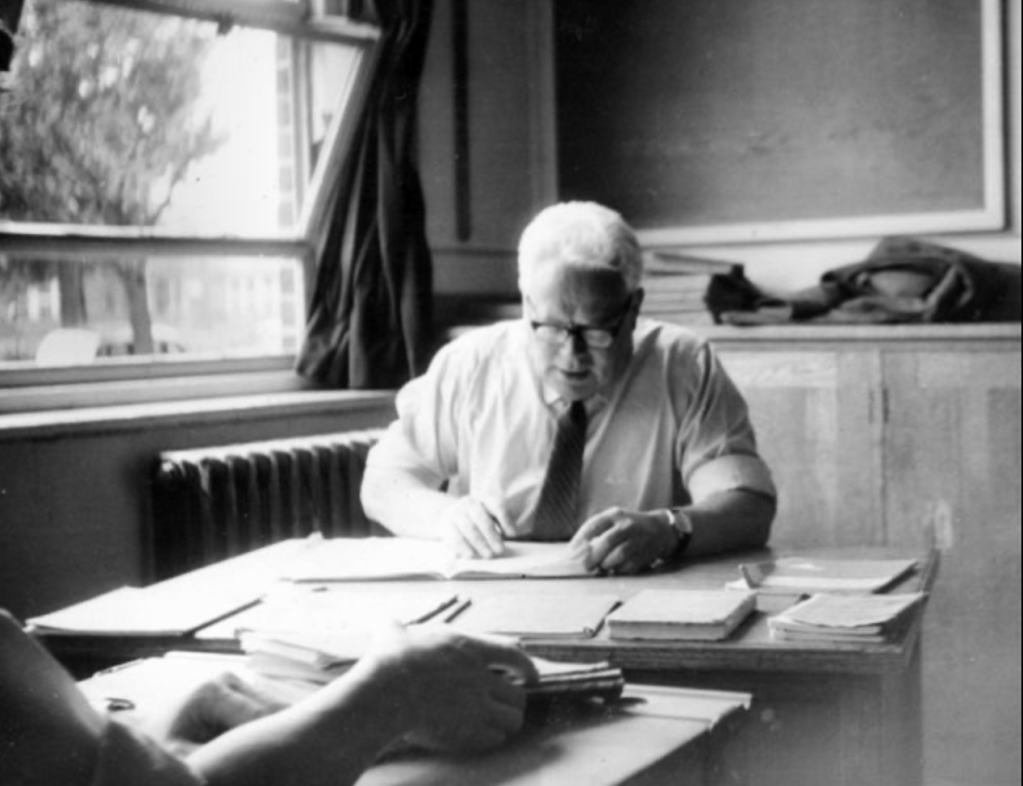

I can’t remember who taught us in the first year. The second, I think (maybe the first), was Jasper Dodds. His name was J.J. Dodds, but at some point boys had decided to name him Jasper or Jaz. This was years, probably decades, before my time. He was Head of History. He had one lung so wheezed horribly and was said to have played tennis for England. He looked ancient, and wore a black gown and dripped snot constantly. He was fond of winding his hands in your hair painfully as punishment (no marks or bruises). We had to sit bolt upright, hands on the desk, and he would put his bony hand under your bottom and wiggle it around to check your posture. He would not last a day in a school nowadays. He had put himself in charge of choosing the Under-12 football teams, which we saw as his opportunity to supervise the communal showers. You had to raise your hand but could not speak until spoken to. Then every sentence had to begin ‘Please sir’ and end ‘yes sir.’

So:

Dodds: Viney. The American war of Independence began in which year.

Me: Please sir, 1776, sir.

He said your name first. He had never heard of the basic teaching technique: Ask a question. Wait while everyone has time to think of the answer. Choose one to vocalise.

He was the only person allowed to use the starting pistol on sports days.

We had six houses (why, I don’t know) and he was the Housemaster of Forest House, who always won at all sports inspired by sheer terror. In those days our houses were older geographical areas in the central South… Avon, Forest, Hambledon, Romsey, Portchester and Twyneham. At least it avoided the controversy of real people names and having to change Nelson House to Seacole House. An odd memory. Once, in the 5th or 6th form, the sports master was away. Dodds took us for gym. He wore his suit with white plimsolls and took us through some ‘pre-war exercises.’ He was very nimble. They were what I later discovered to be effective dance warm up exercises, when we were filming in freezing weather, and Matt Zimmerman, one of the actors took cast and crew through dance warm-up exercises on a tarmac road.

He was a legend. A Bournemouth rock group was named Jasper Dodds. We used to have an annual meeting of old boys at a Tapas bar in Bournemouth which we called ‘The Annual Jasper Dodds Memorial Tapas.’

We were terrified of him. We had to line up outside the classoom waiting for him. We were not trusted in a room without supervision. Only blue black ink could be used and he measured the slope of your writing with a protractor. I once had an essay torn up in front of me for using radiant blue ink. I explained that my father bought my ink, and that’s what he used. ‘That does not surprise me,’ he snorted. ‘What does he do?’ ‘A sales representative for tyres,’ I said. ‘A commercial traveller. Typical,’ he retorted.

Even at 12, I knew he was an appallingly bad history teacher. He wrote his notes from an ancient university exercise book in chalk on the blackboard and patrolled the aisles while we copied them. Our old headmaster’s son wrote on an old school website and pointed out that his father, who started at Bournemouth School just a year before us, had inherited a lot of useless staff, some in senior positions, who he could not get rid of. Jasper was one. Possibly the foremost.

He would report any boy seen without a school cap in the streets, or worse eating in the street. Both were detention offences. He got his comeuppance in the 6th form. About twenty of us rode scooters to school. He put two lads in detention for wearing crash helmets instead of school caps. One’s dad was a police inspector. The father went in uniform and had ‘words’ with the headmaster and had Dodds brought in to the office. We were told by the son that the words ‘idiot’ and ‘cretin’ were brandished. A new rule was instantly instituted: crash helmets had to be worn on scooters.

Then, also in second year six, Dodds was rabbiting on about blue black ink and Bismark, and told an eighteen year old to ‘sit up straight.’ The lad groaned and said, ‘Oh, just fuck off.’ There was silence. The F word had far, far more weight in 1965 than it does today. Then Dodds ignored it and carried on as if nothing had happened. I saw his eyes, and realised he was more scared of us than we were of him. Hence the ultra-disciplinary act.

In the third year, we had Reverend Smith aka The Rev. He was a Baptist minister too, and taught us divinity and history. He had the 17th to 18th century and apologised that his Protestant religious bias was inevitable. He didn’t need to. He always gave both sides. He was cross-eyed, never a good thing in a teacher (You answer next. Who me? No you. Who me? No. no, him.) , but enthusiastic and even excitable on history.

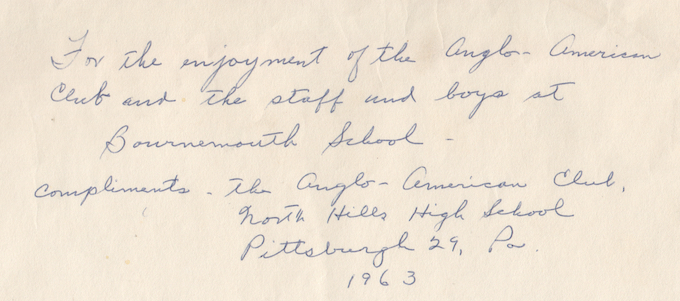

The fourth year changed my life. We had a Churchill Exchange teacher from Pittsburgh. I knew from then on that every snotty Brit comment on American education was wrong. His name was Bob Haubrich from North Hills High School. He gave a slide show on North Hills High School, which looked romantically like every high school movie, and on his travels in Europe, including getting to Leningrad in a VW Beetle.

He was different. He spoke to us as adults. We went straight to original sources for the 19th century. He wrote to the Russian Embassy and issued us with free copies of The Communist Manifesto. He explained that you could not understand the revolutions and late 19th century history without having read it. Oh, and yes. This was deeply Conservative Bournemouth. Several parents complained.

His work on the American Civil War changed my views on history. I’m sure they got me a first on my American History papers years later. The Civil War was a capitalist system versus a feudal system … back to Marx. Sharecroppers in the south were serfs giving over a part of their labour to landlords. Slavery existed in feudal societies. Agricultural economy versus industrial economy. Northern victory was pre-ordained. Don’t be beguiled by looking at generals and battles and tactics. Look at manufacturing industry. Cloth, metal, shipbuilding, railways, arms manufacture. Remember that abolition of slavery was a lesser aim and that it took until 1863 for the Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln thought they should be repatriated to Africa. Robert E. Lee freed his slaves. It’s never simple.

That ran back to the War of Independence. It was little to do with George III’s incompetence, or Washington’s ability as a general. First, it took a minimum of six weeks for a fast boat to cross the Atlantic, deliver an order and return with the response. You can’t govern a country at that distance. Second, the Founding Fathers saw themselves as English gentlemen, but America was often settled by people fleeing religious persecution in Britain. Then you could be transported for poaching a rabbit, or other minor offences, and suffer seven years indentured servitude. The defeated soldiers of Ireland and Scotland were transported to America in large numbers. Or you migrated because you were poor and had no prospects in Britain. Or you were from Germany or the Netherlands. None of these groups had any love for the old country. The British government realised this and when the war started, decided not to transport people to Canada, for fear they would create a population there that disliked the home country too. Again, economically America was much more advanced in 1776 than the British realised. We were given statistics for shipbuilding. Above all, he could teach. He had communication skills, and presentation skills.

A few years ago, I was checking LPs in a charity shop and found Vaughan Meader’s JFK spoof, The First Family. It was an American copy, dedicated to Bournemouth School by Bob Haubrich.

The swine had dumped it on a charity shop. I already had an British copy, but I bought it. One day I will go to Pittsburgh (I’ve wanted to since he told us about it) and present it to North Hills High School. Karen’s great-grandmother spent much of her life in Pittsburgh and we want to research that too.

Skip a year. GCE. All fine. I think Mr Lenton taught us.

Sixth form history. The 19th century. We have discussed this often. Girls schools around us preferred the Tudors and Stuarts for A levels. This may be why the major fiction set in the era is by female authors. Boys schools preferred the 1815-1914 political option.

Our 6th form introduction as a year group was by Mr Dixon, who taught Economics, Economic History, British Constitution and by extension took us for some economic geography. We were in a room with the Economic History students. He started telling us about William of Brittany and the 1065 defeat of Harold III of Essex … then stopped. He said, ‘So you’ve just listened quietly to utter nonsense for five minutes. You cannot do that in the Sixth Form. You have to question.’

How right he was, and how only one of our 6th form teachers followed the advice, Mr Lenton. I wish Mr Dixon had taught us.

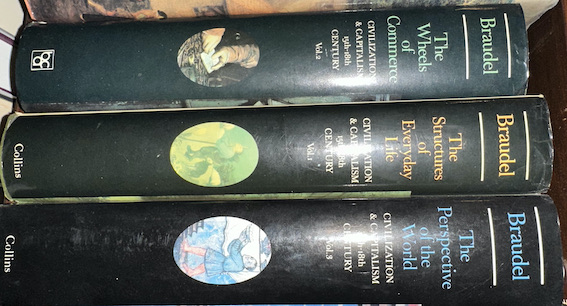

Instead we had Jasper Dodds for European History, Mr Lenton for British. Dodds spoke in fond tones of Bismark, a man he admired greatly, though he thought him somewhat too liberal. Yes, for him 19th century European history was about Bismark, Napoleon III, Victor Emmanuel II, Franz Joseph I and Garibaldi and battles. Not for him The Communist Manifesto. I tried to see the unification of Germany and Italy in wider terms. Napoleon I had created a mood of nationalism, and had set a precedent for national sentiments with his puppet kingdoms. Again, you look at manufacturing and power. Later, I was thrilled to meet the works of Fernand Braudel: history without kings and battles.

You can’t eliminate kings and generals, but you can reduce the list to significant bits. Harold II and William the Conqueror. King John and Magna Carta. Henry V. Richard III. Henry VIII. Mary v Elizabeth. James I / Charles I / Charles II. Cromwell. George III. Victoria. Edward VIII and fascism. Maybe a couple more.

On to Mock A levels. I had a shock in History. Grade A in British. Fail in European. I asked my form master, who told me to see Mr Lenton. This was a very hard one for him. Dodds was his boss. He asked to see my European paper on the Friday. On the Monday he told me he’d double checked it. In his mind it was a straight A grade. He explained that the issue was that I had given opinions, which did not square with Jasper’s views but showed originality and reading outside the main course book. He said that failing it was unprofessional, and he made me promise not to repeat what he said. He assured me I would get an A. I did. When I went in to collect my A level certificates some months after the result, he told me that my papers had been selected to issue to markers as an example of a high A grade. A few years later I met another history teacher socially, who hadn’t actually taught me. He said Dodds should never have been allowed near the Sixth form and the whole department felt the same way.

On History … my older son went to my old school. We had two run ins. This would be 1990 on. The first was when he was given a detention for a ‘disgusting’ essay and I had a note to come and see the teacher- they employed females by then. In my day even the school secretary was male. I asked to see the essay. It was on The Vikings. He had described that a Viking torture was to put a tube down someone’s throat and drop an adder through it. She thought he was sick and needed to see a psychiatrist. I asked to see her the next day. I handed her a book on The Vikings. It was written by a board member of the National Curriculum for history and it was illustrated. We had (and have) a huge collection of children’s school texts on all sorts of subjects, partly for our kids, partly as research for ELT textbooks. It described the torture exactly as he had, and he had read the book. I then asked to see the headmaster to ensure that the detention would be eradicated from his record. I showed him the book. The head said he would have her write and apologise. I said that would definitely not make his life easier in class. Best to leave it there.

Then in the sixth form. He was taught by man who wore a black three piece suit with a watch chain and looked a cross between Rees-Mogg and Dodds. Parents evening. Yes, my son was excellent at history, however he was ignoring advice that every history essay should contain at least six from a list of twelve words he had given them – I can’t remember them all, but they included notwithstanding, aforementioned, nevertheless. I said that surely clarity was the purpose.

He sneered and said rudely, ‘What on Earth do you know about English language?’

Fortunately, the teacher at the next table, overheard and walked over. She had taught ELT from my books. She came over and explained that I was a major ELT author.

‘Which does not qualify you to comment on History.’

I pointed out that my BA in American Studies involved history.

‘I have an honours degree,’ he exclaimed, ‘Second class!’

‘Congratulations.’

I could have pulled rank, I guess, but didn’t add more!

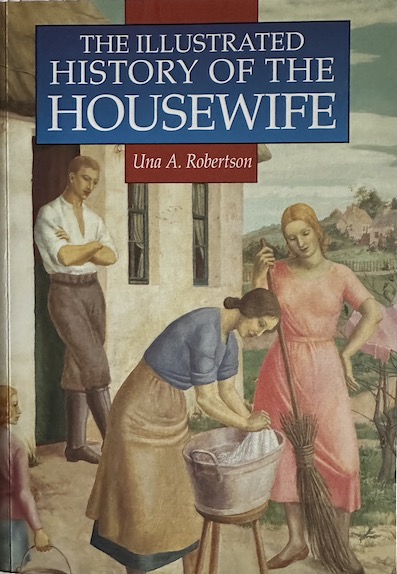

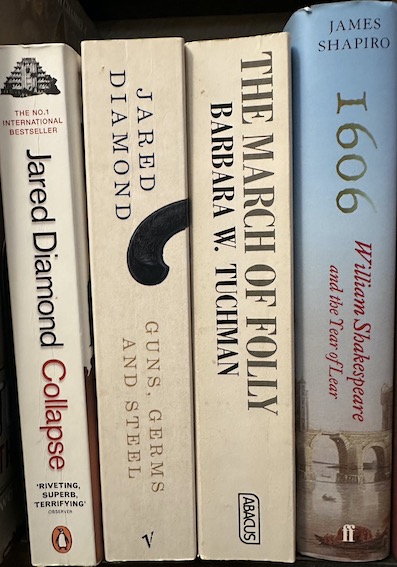

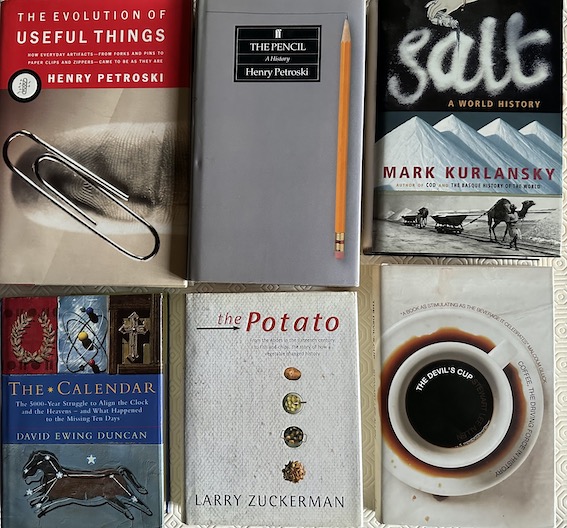

I read a great deal of history. My work on Around and Around on records and record labels is history. Much of what I read is ‘single commodity history’ or ‘single theme history’ or ‘Everything about a year’ … 1066, 1606, 1946.

None of the illustrated would have been considered history by Jasper Dodds.

Nor would these.

Roger commented:

Fascinating Peter. Mr Styles son was in my class and I warmed to him – while sharing your views on the drawing of maps. Oh – have you read The History Of The World In Twelve Maps?

When we moved to Brum form London in 1985 I was interested to note that the head of a local comp was Mr David Swinfen. It had to be…. My work in teacher ed involved me in the life of many schools and I eventually met him – it was indeed he. We reminisced about Bournemouth School but it was obvious to me that he was a little embarrassed over meeting a pupil from what must have been a painful past.

LikeLike

I shuddered reading this, especially with the photographs; I was a meek boy when I was there, joining in 1962 in Form 1.12, and initlally all was as expected….. by the time of leaving, I was a nervous wreck, I imagine it was PTSD, and finished up in the lowest of the low, 5.7, departing the school in 1967, and later doing A levels at college which had a less oppressive manner…. became an IT and Projects Manager, so achieved something like the same status I would have received, only later…… Bennett was dreadful, a good cure for constipation, but Barraclough, his deputy, was a rather kind man, and a golfer, where I worked initially. Mr Veater was the French teacher, but I refined my accent from the Portsmouth one I inherited from him. I still ger flashbacks, and wonder whether I would have been better with Dan Crone at Summerbee…… too old to wonder now, 74 at Christmas…. but it was sometimes like a Victorian workhouse, similar to the gruff grandfather I had, but who softened a little when he died, when I was aged 14…… we had it tough….. Jasper Dodds also had a habit of punishing you for smallish things, and would make you write out a side and a half of your best writing, to give him – which I would feverishly write as fast as I could, and despite being left-handed, was really neat….. perhaps I was a little devious after all…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Martin. On Ernie Veater, see Language Learning in Britain Past!

LikeLike

I guess we could all tell a tale or two about the lovely Mr Bennett and the charming Mr Dodds. My father was at the school when it moved from Porchester Rd to East Way. Jasper was there then and apparently even more scary as a younger/stronger version. I am fairly certain Mr Cutler had become Adge by the time he taught us. Either way, he used to call into my office in Charminster Road the 90’s. By then I felt he had improved somewhat. Hello to Martin above (no relation).

LikeLike

I have

LikeLike

I have mainly happy memories of my time at Bournemouth School. My time there was only in the 6th form, 1962 to1964 but I so enjoyed reading Peter’s article since it brought memories of the characters at the School at that time. Nearly every boy had there own way of impersonating Jasper , but fear really existed in the presence of Mr Bennet.

if anyone has access or knows how to get access to the School magazines of my time at the School Autumn 1962 to Summer 1964 it would be greatly appreciated since I would love to show them to my grandchildren.

Thank you again Peter.

LikeLike