by Tanika Gupta

Directed by Pooja Ghai

Designed by Rosa Maggiora

Music and sound by Ben & MaxRingham

The Swan Theatre

RSC, Stratford-upon-Avon

Saturday 29th July 2023, 13.30

CAST

Raj Bajaj- Abdul Karim

Miriam Grace-Edwards – Charlotte / Georgina

Francesca Faridany – Lady Sara

Alexandra Gilbraith- Queen Victoria

Aaron Gill – Hari

Anyebe Godwin – Serang / Lascar

Oliver Hembrough – Lord John Oakham / William / Painter

Avita Jay – Firoza

Tanya Katyal – Rani Dad

Tom Milligan – Freddie / ensemble

Sarah Moyle- Mary / Susan Matthews

Chris Nayak- Jinnah / Singh

Lauren Patel- Ruby / Asha

Simon Rivers – Dadabhai Naoroji

Anish Roy- Gandhi / Lascar

Nicola Stephenson – Lascar Sally

Premi Tarang – Lascar / Ayah

Joe Usher- Lascar

MUSICIANS

Madhusoodanan Satchithanandan – bansuri

Vikaash Sankadecha- percussion

Carolina Lopez del-Nero- cello

Hinal Pattani- keyboards

It’s a tenth anniversary production of The Empress which was first performed at The Swan in 2013, and directed by Emma Rice then. I’m sorry I missed any Emma Rice directed play. The play is already a set GCSE book. I worry about plot spoilers, but so much happens during the play that this outline will still leave much to be surprised at.

The play weaves three stories together. The central story is Rani, a 15 year old ayah (nursemaid) at the start, and Hari, a Lascar (Indian sailor). Their romance is interrupted, and many years pass before the eventual happy ending. Then we have the true story of Abdul Karim, and how he moved from servant to Queen Victoria to Munshi (teacher). The third strand, also true, is Dadabhai Naoroji, the first Indian Member of Parliament in Britain. A young vegetarian teetotal and chaste lawyer named Ghandi appears on the boat to Britain with him. Whatever happened to him?

It gets off to a vibrant start with the ship at sea in a storm, on its way from India to Britain. This is the RSC. They are used to doing initial shipwreck scenes after all. This is one of the best (not that it gets wrecked). The sailors climb the rigging singing something that sounds like Bless ‘Em All.

The story spans fourteen years. The ship arrives in Britain for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887. By the Diamond Jubilee in 1897, Abdul Karim is fully established at her court. It continues until Victoria’s death in 1901. During which Rani has been abandoned in London, been made pregnant, had a baby, abandoned her, picked her up again, learned to write in English, become a secretary to the politician, and finally is there with the 12 year old daughter. They don’t hang about. The direction is fast moving, the scenes flow rapidly into each other. They pack a great deal of narrative into the time. The visuals fill in unspoken parts of the story. As the sailors and passengers discuss the exploitation of India, the sailors carry a huge ivory tusk onto stage and lay it down. No one points it out. Shortly it’s carried off. There is constant movement of boxes, cases, everything. The cast are forever changing costumes, so Oliver Hembrough is the rapacious Lord “call me John” Oakham, a porter, a priestly political supporter of Dadabhai Naoroji, a cheerful brothel visitor, a member of the household cavalry and a soldier and probably other roles too.

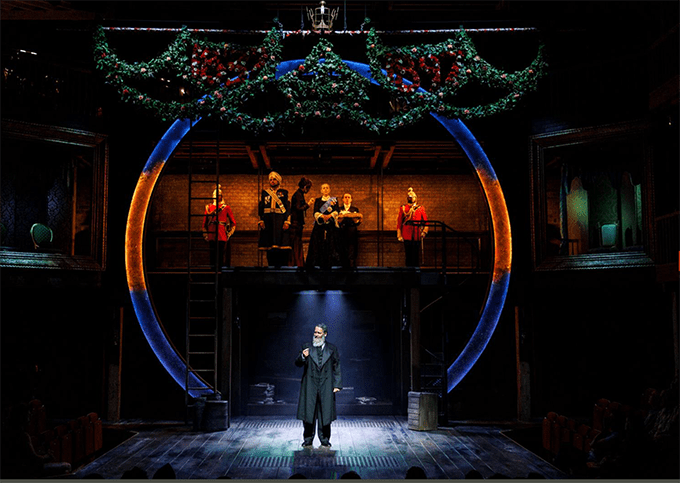

The set (like Hamnet at The Swan earlier this year) utilises a high metal central platform with ladders to create a second acting area. Possibly this is a fixture after the Swan rebuild last year. This is the location of most of the Queen Victoria scenes. At each side, an ornate picture frame surrounds a “box” at a theatre where Victoria and Lady Sarah sometimes appear and sit. Then under the platform, we have a room set – a Shakespearean inner stage, but it slides out to the front when needed.

A minor note on costume. Rani’s original sari is white with a green trim. When she carries her orange handbag, the result is orange / white / green. The Indian national flag. On the boat, Rani meets Hari, a sincere young Lascar. They bond over The Ancient Mariner.

Rani is abandoned in England by her employer, who just wanted her as an ayah for the voyage, and lied that she was giving her enough money for a return passage to India (that’d be a good title for a book). Hari rescues her, and takes her to Lascar Sally’s, a raucous brothel, where they can spend the night. As the madam, Lascar Sally is the definitive tart with a heart of gold.

Hari is a little too free with his advances and Rani flees into the night. They are not to meet again for many years. Rani eventually finds employment as an ayah to Lord and Lady Oakham. Lord Oakham grew up in India and has a taste for curries and women in silken saris. He has perhaps studied the Kama Sutra too closely.

This is the inner stage set that slides forward when in use.

You can guess what friendly aristocrats do to young female servants. We once visited a stately home (a special theatre visit- it wasn’t open to the public). Karen mentioned to the cheerful resident lord that her ancestors had been humble workers in the same village. He roared with laughter and said, ‘We’re probably related then.’ She turned it right back, ‘We could be. My ancestors were very good-looking men.’ Anyway, Rani gets pregnant. More broken British promises evaporate and she is thrown out. Lascar tart-with-a-heart Sally rescues her, and the trio of women working together will include Firoza (Avita Jay) an older ex-ayah who suffered much the same fate. Meanwhile Hari is trying to start a sailor’s trade union and being brutalised for his troubles. He manages to get letters to Rani before being dumped off the boat at Cape Town.

They are thousands of miles apart she is looking at his letters, while he speaks the lines from them

The three women get involved with a Christian mission to help abandoned ayahs, and there she meets Dadabhai Naoroji again, and he remembers her from the voyage. She goes to work for him, which pulls those threads together.

Dadabhai Naoroji (Simon Rivers) gets the major speeches about British iniquities.

The other theme is interwoven, and until right at the end operates separately, except that Abdul Karim was on the boat at the beginning. Karim is a Moslem, Dadabhai Naoroji is a parsee, Rani is Hindi.

Victoria was partial to a burly bearded bloke in ethnic costume, like John Brown and Abdul Karim. Abdul Karim (Raj Bajaj) has been sent as a servant, as a gift to her. Alexandra Gilbraith’s Queen Victoria is a fetching and funny performance. You just don’t think of Queen Victoria (we are not amused!) as such a bright, funny lovable character. She draws the audience so much onto her side that when she gives the snooty Lady Sarah (Francesca Faridany) a good telling-off, there was spontaneous applause.

We feel saddened when Lady Sarah reports that Lord Salisbury, the prime minister, and Bertie, the Prince of Wales (Edward VII), are ganging up to pressurise her to downgrade Abdul Karim and will declare her insane if she refuses. The three, snooty Sarah, assertive Victoria and the cunning, proud but manipulative Abdul Karim are a trio you always want to see more of.

We’ve met Karim on the boat, when he is disparaging about Hari and the Lascars, looking down on them, just as Lady Sarah will look down on him. We empathize with Karim as after Victoria’s death (her open coffin is incredibly realistic) he is stripped of all honours and letters and mementoes. He is something of a philosopher, though like Indian gurus such as the Maharishi, he combines genuine helping with his own advantage. This could have been a play in itself. But then so could the Rani / Hari romance.

Abdul Karim says that as Queen Victoria can’t travel to India, he will bring India to her. This is a marvellous late scene. The highlight is Tanya Katyal as Rani doing a long solo Indian dance. We were transfixed. For Karen, it was the theatrical moment of the year so far. She desperately wanted to study Indian dance, but after a week barefoot on wooden floors the teachers stopped her. Unlike the other dance students, she was leaving trails of blood on the floor. She couldn’t do it (or rather no one wanted her to make the floor slippery). She still loves it and noted the hand movements, and explained at length afterwards the physical prowess needed. The music was sublime … Karen also introduced me to Indian music. I notice that the RSC photo galley online does not include the scene, and they’re right. Keep it as a sensational and sensual surprise.

The music was by a four piece – bansuri is a kind of flute. They could play Western chamber backing with cello or piano, or sound totally Indian. I have to assume that the sitar like sounds were generated from the keyboard.

This is the 1897 Diamond Jubilee, with the royal party above while Dadabhai Naoroji gives his major political speech.

Accents interested me. On the boat any trace of Indian accent is very light to non-existent. It is very light when Indians are speaking among themselves. When forced into confrontation with the British (and their hirelings) the accents instantly switch and become much stronger. It works. I know the last few years of ELT recording, we worked with several Indian actors who had no accent whatsoever in conversation or on microphone, but would do an accent if we asked. A major point (and an issue with all those telephone call centres in India) is that Indian English is a strong and distinct native speaker dialect. I had a Sikh colleague who had no Indian accent whatsoever. He explained that he was twelve when he arrived in England, his parents could not speak English so he learned from school. That is, he never learned Indian English.

Quentin Letts in the Sunday Times complained about the necessary coincidences needed to weave the three stories together (brilliantly executed for me), and disliked the political speeches on British Imperialism. They are all true though. On the other hand, India has never been noted for gender equality, inter-religious tolerance or lack of racism. Racism is built deep into the caste system. My son spent many years in China and then many months in India studying martial arts. He found the poverty, and the attitudes to the poor in Southern India far, far crueller than anything he ever saw in deepest rural China. However, this play highlights the issues for 19th century Indians in the merchant navy and on arriving in Britain, and that’s all true. You can’t argue it, and for British people of Indian origins it’s a highly inspiring play. (We felt inspired too.)

It’s long, running three hours, but it never felt it. At the end we just wanted more. A triumph. Five stars from both of us. Curry for us tonight!

*****

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

five star

West End Best Friend *****

four star

Nick Ahad, The Guardian ****

Donald Hutera, The Times ****

Birmingham Post, ****

three star

Quentin Letts, Sunday Times ***

two star

Anya Ryan, The Stage **

LINKS ON THIS BLOG

ALEXANDRA GILBRAITH

Cymbeline, RSC 2023 (Queen)

The Provoked Wife, RSC 2019

The Lie, Menier Chocolate Factory, 2017

The Rover, RSC 2016 (Bianca)

The Merry Wives of Windsor, RSC 2012 (Mistress Ford)

CHRIS NAYAK

King Lear, Globe 2017

Much Ado About Nothing, RSC 2015, 2016 (Borachio)

Love’s Labours Lost, RSC 2015, 2016

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, RSC 2016 (Demetrius)

AVITA JAY

Comedy of Errors, RSC 2021

The Winter’s Tale, RSC 2021

RAJ BAJAJ

Tamburlaine, RSC 2018

Tartuffe, RSC 2018

OLIVER HEMBROUGH

Echo’s End, by Barney Norris, Salisbury 2017

SARAH MOYLE

Women on The Edge of A Nervous Breakdown, London, 2015

The Spire, Salisbury 2012

Leave a comment