The Caretaker

By Harold Pinter

Directed by Justin Audibert

Designed by Stephen Brimson Lewis

Composer Jonathan Girling

Chichester Minerva Theatre

Saturday 6th July 14.15

CAST

Adam Gillen – Aston

Ian McDiarmid – Davies

Jack Riddiford – Mick

SEE ALSO: My review The Caretaker, by Harold Pinter, Old Vic, 2016. This has extensive notes on the play and its background. The play is such a classic that readers here probably have an idea of what it’s about. Aston is a victim of Electro-Convulsive therapy. He rescues a tramp, Davies, from a beating up and offers him a place to stay. The dilapidated attic flat belongs to Aston’s brother Mick, who is a fast talking hard man. Davies is offered the job as caretaker, generally ‘keeping an eye’ on things.

This is the second of three Harold Pinter plays we have booked for this year, and by Chichester’s new artistic director, Justin Audibert. We know his work from the RSC, which is where Daniel Evans, the previous artistic director has gone.

When I’m 64

When we saw the play in 2016 with Timothy Spall and Daniel Mays, I thought the acting was superb, but the play itself was showing its age. It was first performed in 1960, so it is now 64 years old. I realize that placing it in the ‘modern’ section of reviews here is becoming increasingly daft.

It’s hard to find much to say as Pinter’s biographer, Michael Billington, did the programme notes and pretty much summed it up.

I note that at two least reviews compared it to Waiting for Godot, with three speaking characters. I had never felt that before, but in this production there was something about the timing and phrasing of lines that had a Beckett aspect.

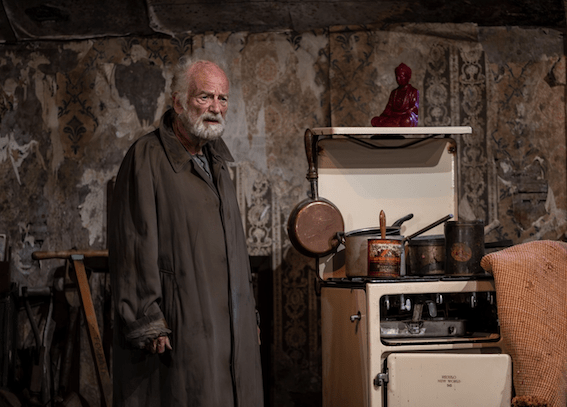

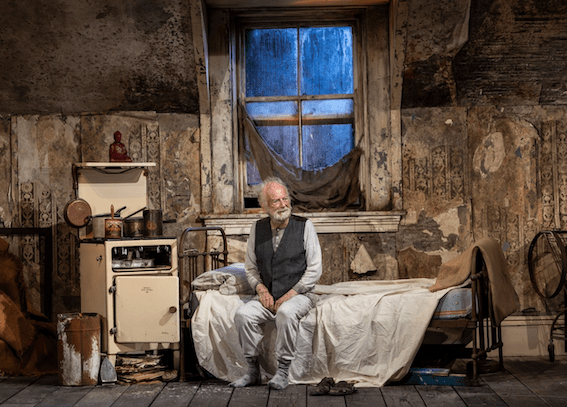

In terms of set design, it’s the absolute opposite of Godot. You have to have a detailed set, you have to have a gas stove, two beds, a sash window, a bucket catching drips, an electrical appliance for Aston to try to repair, lots of wood, a pile of old papers, suitcases with sheets, boxes with shoes, a light bulb that could be removed to fit an Electrolux vacuum cleaner. NOT a Hoover. It is described by Mick as ‘an Electrolux.’ I suspect Pinter was wary of the letters Hoover used to send whenever they found someone using their brand name generically. The letters never worked. I’ve just been hoovering with our Dyson, though I’ll hoover the garage with the Henry.

It always is detailed, but this set by Stephen Brimson Lewis must be as detailed as it’s possible to get.

We were right at the front. I stared at that pile of old papers and started itching my hand as if I’d been afflicted by book mites. It didn’t stop. We wondered where they had found the perfect enamelled gas stove.

They even created a ceiling. This is obviously a photo ten minutes before the play started, but Mick was already on, staring disconcertingly at the audience, making eye contact too.

That Godot effect was emphasised by the music. Jonathan Girling has managed to channel a modern version of the sort of slightly staccato jazzy sounds popular on avant-garde films in the early 60s. Not only that, stage movements, shifting the junk props, dressing, getting into bed, were choreographed to the soundtrack in subtle ways. Maybe they just seemed to be. At the end of Act two Adam Gillen as Aston delivers the monologue about his ECT therapy, and gentle violins took over the background. Overall, the music was brilliantly supportive.

We certainly have a five star set, and a five star musical accompaniment. All three actors deliver the sort of performance that almost leaves you unable to imagine playing it another way. As Billington points out, these three roles have been interpreted very differently over the years, the hallmark of a great play.

Ian McDiarmid is Davies, the tramp. He’s just been beaten up. McDiarmid plays him as someone we suspect has seen better days. He’s not got a heavy regional accent, rather well-spoken underneath, even slightly camp. He veers between gratitude and querulous complaint- the shoes don’t fit, he’s in a draught, Aston has a better bed.

He’s also mentally ill and vulnerable, or at least has dementia. He worries about the documentation he left with someone in Sidcup, during the war, fifteen years ago. Has he been abroad? Was he in the RAF? That reminded me of a tramp who’d accost people in Bournemouth with, ‘Excuse me … weren’t you in the RAF?’ As many were forty years younger, it seemed unlikely. If he found someone who had been in the RAF, he’d ask which base. That allowed him to claim he was there too and ask for money.

Then Adam Gillen is Aston. Odd stance, odd set of the mouth, insecure way of walking, speaks hesitantly. His OCD comes out in the jerky way he lays his trousers, jumper and tie on the bed so precisely. Yet he is kind and generous to the old man. The speech about his own mental illness which closes Act Two is an acting triumph.

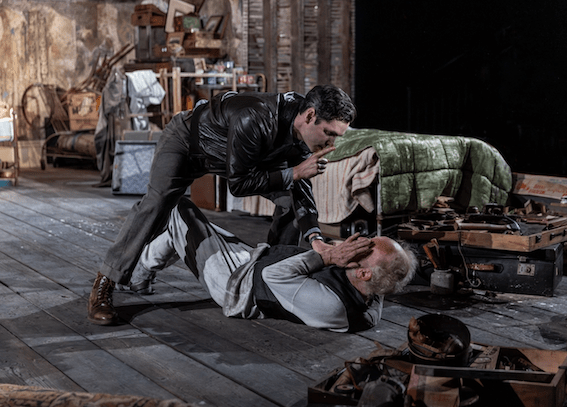

Mick, the volatile and voluble brother is Jack Riddiford. Bullying, taking the piss, threatening yet defensive as soon as Davies starts to criticize Aston. 1960? The semi-humorous bantering but aggressive stye reminds me of portrayals of the Kray Brothers circle.

The powerful three roles is the appeal of the play.

As in 2016, Karen was particularly taken with the accuracy of Pinter’s portrayal of mental issues. In 1970 she was working at the local psychiatric clinic. Aston is how Electro-Convulsive “therapy” genuinely presents. At that point they were using it for a very wide range, including girls with anorexia. She saw a number. Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest has them totally zombified, but either they used higher voltage in the USA, or he was writing for effect. Then Davies, the tramp, was a portrayal of another regular type of client at the clinic.

On the other hand the fast talking and aggressive Mick reminded her more of the policemen trying to bully information about patients from the staff. They used to boast about beating up tramps on a Friday night and hosing them down too. Pinter avoided that by having Davies talk about being beaten by a ‘Scotch.’

The other programme essay is on immigrants and Davies and his dislike and fear of all of them … blacks, Indians, Greeks, Poles. As one of the filthiest people imaginable, he worries that their hands have contaminated the banisters. You couldn’t get anyone filthier unless you’d wafted the smell of ancient urine into the auditorium. I’m glad they didn’t. Karen would get on a bus or walk into W.H. Smith, sniff, and say ‘a tramp’s been in here.’ The smell was prevalent in the clinic.

It was apposite listening to this two days after the 2023 general election where Reform got 4.1 million votes. The first reaction was that the votes were taken from Conservative, just further over to the right. I’m not so sure. I believe politically the great social divide is between those who earn a living from the state … teachers, nurses, care workers, civil servants, local government employees, police officers, university lecturers and vice-chancellors, high court judges, consultant surgeons … and those who work for private companies or for themselves. In the ‘living from the state’ group you have the very wealthy and the very poor. The thing is for the “educated” in both groups on the divide, immigration is a positive, to be embraced. I think of our very good Polish friends, the Romanian manager at our local NatWest, the Portuguese window cleaner, the Nigerian surgeon and the Sri Lankan nurses who looked after me in hospital, the Spanish charge nurse who changed my dressings, my Indian chiropractor, the Filipinos who wiped our older relatives bums in the care homes, the polite and cheerful Amazon delivery driver from Syria, the taxi driver yesterday who was from Mongolia. The one last week who was Libyan. OK, we do see the odd Middle Eastern refugee in a shop doorway, but we can put a pound coin in the plastic cup and walk on with a warm glow from our generosity and compassion. It’s not like that at the bottom where Aston and Davies reside. Immigration means competition for jobs, undercutting wages, jumping up the queue for council housing, speaking incomprehensible languages in the corner shop. That’s where Reform spreads its foul message. When Pinter was writing this in 1960, the same atmosphere existed. In the 2016 production, it seemed more like a throwback to 1960’s Commonwealth immigration and Enoch Powell. Not in 2024. It’s all current.

The play was advertised at two hours ten minutes including interval- it’s ten minutes longer than that. We were so enthralled that we wouldn’t have noticed, but we’d planned to drive home for the England v Switzerland Euros game to get back for at least the second half. (A motorway crash ahead of us stymied that).

In 2016, I thought the acting was superb, but the play itself creaked. It creaked far less this time. Times have changed. We’re now familiar with homeless people in shop doorways all over the town centre. Boarded up shops in crumbling malls. The times have caught up with the play again.

The style of the production augurs well for Justin Audibert’s new regime at Chichester.

*****

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

5 star

Jill Lawrie, Theatre South East *****

4 star

Daily Telegraph ****

Gareth Carr, What’s On Stage ****

Dave Fargnoli, The Stage ****

Nick Wayne, West End Best Friend ****

3 star

Ryan Gilbey, The Guardian ***

LINKS ON THIS BLOG

HAROLD PINTER

The Lover / The Collection by Harold Pinter, Bath Ustinov, 2024

The Birthday Party, by Harold Pinter, West End 2018

The Birthday Party, by Harold Pinter, Bath Ustinov 2024

No Man’s Land, by Harold Pinter, 2016 with Ian McKellan, Patrick Stewart

The Caretaker, by Harold Pinter, Old Vic, 2016

The Caretaker by Harold Pinter, Chichester Minerva, 2024

The Homecoming by Harold Pinter, Trafalgar Studios

The Hot House by Harold Pinter, Trafalgar Studios

Accident (film) 1967

JUSTIN AUDIBERT (Director)

The Taming of The Shrew, RSC 2019

Snow in Midsummer, RSC 2017

The Jew of Malta, by Christopher Marlowe, RSC 2015

Flare Path by Terence Rattigan, Salisbury Playhouse 2015

IAN McDIARMID

The Merchant of Venice, Almeida, 2015 (Shylock)

ADAM GILLEN

Amadeus by Peter Shaffer, National, 2017 (Mozart)