The Browning Version

By Terence Rattigan

Directed by Michael A. Simpson

BBC Broadcast, 31 December 1985

CAST:

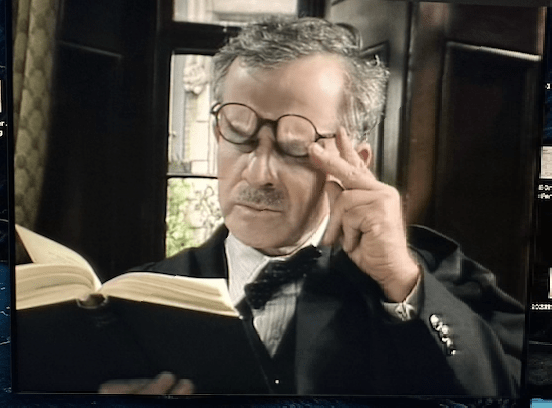

Ian Holm- Andrew Crocker-Harris

Judi Dench – Millie Crocker-Harris

Michael Kitchen – Frank Hunter

John Woodvine – Dr Frobisher

Steven Mackintosh- John Taplow

Shaun Scott – Mr Gilbert

Imogen Stubbs- Mrs Gilbert

The fourth from BBC’s The Rattigan Collection. As usual they employ major actors, here Ian Holm and Judi Dench.

The play dates from 1948, when it was performed as a one act play, followed by Harlequinade as the second act. The pair were called Playbill. It’s a strange combination. The pairing requires two radically different sets. The Browning Version is sad, poignant, and said to be Rattigan’s favourite among his plays (Michael Billington chooses The Deep Blue Sea as the best in 101 Plays.) Harlequinade is a farce. They were played by the same cast, so Rattigan was in the same mode as the later Separate Tables, stressing the range and versatility of actors. Perhaps he wanted to depress then lift the audience … we watched The Browning Version, then after a break, watched an episode of the original Frasier to cheer ourselves up. In recent years, the tendency is to perform the plays separately, though they are in one volume in print (labelled ‘The Browning Version’ on cover and spine). Kenneth Branagh paired Harlequinade with the solo All On Her Own. Like most Rattigan plays The Browning Version went swiftly to film in 1951. Then it was redone in 1994. Both were padded out with exterior shots to extend it beyond its 75 minutes stage time. This version dates from 1985 and starts with a minute and a half walking past a cricket match and through the school.

New Year’s Eve was a premium broadcasting spot, particularly for a play perhaps aimed at those who weren’t going out. It is set about when it was written. Rattigan and Coward plays don’t shift far from their time periods.

The original Playbill pairing did better in London than New York. I’m not surprised. Try explaining Lower Fifth, Upper Fifth, Remove. Lords (cricket ground). I don’t understand what the Remove form is either and Googling reveals that it was a different year group in different schools. In Billy Bunter books, it’s the Lower Fourth while here it seems to be after the Lower Fifth. We had a Five Remove at my state school, but that was repeating GCE to get better results, so the same year as Lower Sixth. We move in different social circles. Add some bits of Ancient Greek. In my memory the play gets confused with Goodbye Mr Chips, and Rattigan name-checks that earlier play here.

The play takes inspiration from characters from Rattigan’s schooldays at Harrow, particularly his Classics tutor J.W. Coke-Norris, who becomes A. Croker-Harris. He concealed that link well then. Who would ever guess? Ah, sweet revenge. Coker-Harris (Ian Holm) is a classics teacher and it’s his last day at the public school after eighteen years. He is feared by the boys. He is strict, and dull. In the play he speaks about his teaching career and how and why he moved from trying to be liked to settling with being a feared stickler for discipline and the school rules.

There is a classroom management lesson there. My co-author, Bernard Hartley, was a great teacher trainer. One of his maxims on teenagers was, ‘If you go in trying to their jokey best friend at the beginning, they will pin you against the board. So you will end up presenting as Hitler with a bad headache. So, you should start off as Hitler with a Bad Headache, and gradually relax and become genuinely friendly.’ It’s interesting in The Winslow Boy, we first see the father as fierce and demanding, then we get to know him.

ASIDE: I have thoughts on this. Often the eventual ‘Hitler with a bad headache’ figure is concealing their own fear. At my grammar school the head of history was J.J. Dodds, known to all as Jasper. He had played tennis for England (according to school rumour) and had one lung. He wore a gown and terrified the kids. We could only write in Quink Blue-Black ink. He would measure the slant of our writing. He twisted your hair agonisingly. He was forever making us sit up straight, no elbows on desks, carefully checking the extreme bases of spines with bony fingers … I know. Nowadays he wouldn’t last long doing that. We knew it was dodgy then. To speak, you had to raise your hand and begin ‘Please, sir ….’He also dripped snot. I will state that he was an appalling teacher, regurgitating his university notes from thirty years earlier, writing them on the board, making us copy while he checked handwriting. We got to the Sixth Form. He was just as bad. In the second year Sixth, on a hot day, he was going through the whole blue-black ink, angle of letter stuff. He told a lad, a 17 or 18 year old, that the slant on his writing would be unacceptable at A -level (which was imminent). The lad groaned, ‘I’ve had enough of this. Just fuck off.’ There was silence. Jasper froze. The most feared teacher. Detention? A trip to the headmaster? Expulsion? Instead he totally ignored it and launched into a talk on Bismark, his favourite historical figure. I was staring at his face. I knew then for certain that he was absolutely terrified of us, way more than we were of him, hence the whole disciplinarian act. His bluff had been called. At that point, we were adult enough not to take advantage of it. I will come back to this.

The play starts with Taplow (his first name is in the cast lists, but he wouldn’t have had one) entering the empty apartment / study of Croker-Harris. Rattigan’s play texts are not as explicit as Coward’s, but he still writes the specific stuff that annoys directors:

He is a plain, moon-faced boy of about sixteen, with glasses …He is dressed in grey flannels, a dark blue coat and a white scarf …

This director totally ignored it. Rattigan would have said it gave a sense, and if you don’t like it, think of something better. Mr Croker-Harris is ANDREW in the script and his wife is MILLIE. Hunter is FRANK. Not that we hear those names often.

Taplow goes to a box of chocolates, extracts two, eats one, thinks, and puts the other back. Thus Rattigan has set a question for the play. Taplow is not entirely honest, and in 1948 sweets were so rationed that a single chocolate might be a week’s allowance. So why does he put the second one back? Is he cunning and thinks two might be noticed? Or does his conscience prick him because basically he likes Croker-Harris?

Taplow picks up a walking stick and pretends to do golf swings. A young science teacher, Hunter, comes in behind him, and corrects the golf swings. Hunter asks what he’s doing next year and Taplow says he’s interested in science. ‘Yes, we get all the slackers,’ responds Hunter. Britain’s problems with technology start there – classics were more highly valued.

They talk about Croker-Harris, and Hunter is remiss in letting the boy go too far and do imitations. Taplow explains that he quite likes Croker-Harris, though his classes are uninspiring routine translating around the class (I’ve been there, done that). He’s waiting for tuition even though it’s the last day of term. He is hoping that Croker-Harris will recommend him for the remove (whatever that is) the next school year.

Mrs Croker-Harris (Judi Dench) arrives. She sends Taplow off to get her husband’s prescription in the village and gives him money for an ‘ice’ too. Her husband has heart problems, hence the early retirement from the public school. He is going to a less arduous role at a ‘crammer’ in Dorset. It starts icily. Hunter was invited to go to Lords with them but ‘forgot’ and went with the headmaster to a box instead. They had paid for his ticket too. (This may be why this TV version opens with a cricket scene). The conversation reveals that Hunter and Mrs C-H (or Millie) are having an affair. Hunter is invited to dinner that evening and they are planning to meet in the summer holidays in Bradford (Rattigan does have a sense of humour).

When Croker-Harris gets back, the tuition resumes, and they discuss Aesychlus’s Agamemnon.

CROKER-HARRIS: When I was a very young man, only two years older than you are now, Taplow, I wrote for my own pleasure, a translation of the Agamemnon – a very free translation – I remember in rhyming couplets.

ANDREW: The whole Agamemnon – in verse? That must have been hard work, sir.

CROKER-HARRIS: It was hard work, but I derived great joy from it. The play had so excited and moved me that I wished to communicate, however imperfectly, some of that emotion to others. When I had finished it, I thought it very beautiful – almost more beautiful than the original.

Croker-Harris can’t find the manuscript. The point is that in his own teaching, he has totally failed to communicate that joy, trudging pedantically through, line by line.

They are interrupted by the Headmaster, Dr Frobisher.

Rattigan describes him: He looks more like a distinguished diplomat than a doctor of literature and a classical scholar. He is in his middle fifties and goes to a very good tailor.

Here in this BBC version, we are post Lindsay Anderson’s If …. And they have gone for the same type. A smooth urbane CEO, not a ‘classical scholar’ at all. The type who will be introducing Business Studies and Economics as soon as he can get rid of his ageing classics-oriented staff. He does not wear a gown.

Frobisher is a total bastard. Taplow is sent packing and they are down to business. He begins by praising Croker-Harris as the greatest classical scholar they’ve had. Two major prizes at Oxford. Twenty years is the line for a pension, which is granted at the whim, or discretion, of the governors. 1948. Just before National Insurance and universal pensions in Rattigan’s mindset. Eighteen? Croker Harris does not qualify. The headmaster quizzes him on income. He had thought that Millie’s boasting of family connections meant they were of independent means. No? Bad luck. It is pointed out that Buller, injured in a rugby match, qualified for a pension after just a few years. Ah, but Buller was a popular fellow. 500 people signed the petition to award him a pension.

Then we come to Leaving Day. The headmaster announces that Fletcher, who is leaving for a job in the City, will be speaking AFTER Croker-Harris. He was only there five years, but he will take precedence over Croker-Harris. Why? Well he is so much more popular.

FROBISHER: You really mustn’t take it amiss, my dear fellow. The boys applauding Fletcher for several minutes and yourself say – for – well, for not quite so long – won’t be making any personal demonstration between you. It will be quite impersonal – I assure you- quite impersonal.

Millie returns and the Head leaves, or rather slimes off. She quizzes him about the pension. She is incensed. They won’t have enough money to live on.

MILLIE: So what did you say? Just sat there and made a joke in Latin, I suppose.

Then The Gilberts arrive. Mr Gilbert is replacing Croker-Harris. They are newlyweds. This will be their first home. Millie shows the wife around the flat.

This is where Gilbert can ask Croker-Harris about teaching, and teaching 16 year olds. This is where Croker-Harris talks about how he wanted to communicate enthusiasm and failed. Then he changed as a teacher. How he played up mannerisms to get laughter. Then the boys stopped finding him funny. Gilbert reveals what the headmaster told him. The boys know Croker-Harris as ‘The Himmler of the Lower Fifth.’ He finds this deeply upsetting.

Taplow returns. He came back to say goodbye. Incidentally, I feel Rattigan is really stretching the abilities of the acting profession by putting the words to be said in Greek in the Greek alphabet. Ezra Pound annoys in the same way. Pretentious, με? Or could the actors of 1948 have just read it?

This is where the Browning version, his translation of the Agamemnon, comes up. Taplow has bought a secondhand copy and written an inscription to Croker-Harris God from afar looks graciously upon a gentle master. He is moved to tears by the kindness and appreciation. He has to ask Taplow to fetch his medicine.

Hunter returns for dinner. Taplow leaves, and Millie comes in. Croker-Harris shows them the inscription.

Millie scoffs, mentions she heard Taplow imitating him and claims the gift of the book was ‘a few bob’s worth of appeasement’ so that he would be recommended for the remove (whatever that is again). Andrew leaves the room. Hunter is furious at her deliberate cruelty and declares he will have nothing more to do with her.

In the subsequent conversation between Hunter and Croker-Harris it is revealed that he knew all about the affair. Hunter was the last in a long line of younger teachers.

Croker-Harris says he was not equipped for that type of love and so Millie is to be pitied. Hunter asks if he may visit him in Dorset. The play ends with a phone call from the Headmaster. At last Croker-Harris asserts himself. He will NOT speak before Fletcher.

There is the question over the gift. I interpret it as genuine, as did Hunter. Where would a boy find a second-hand bookshop after six in the evening?

It is poignant. It is sad. Let me return to my old history teacher. I was told this tale a few years ago, I wasn’t there. Jasper drove an ancient dusty black car, possibly to match his dusty black gown. One evening he was outside the school, vainly trying to start it. A group of boys walked over and volunteered to push start it. He was surprised. He also knew no one liked him. There was a catch in his voice as he thanked them profusely. They indeed push started it, and watched it sail off into the distance. Inscribed in the thick dust on the boot, it now said ‘Jasper is a c*nt.’ (Apologies to American readers. This was common currency in boys schools in the UK) There were no repercussions. The car arrived the next day freshly washed. I roared with laughter when told the story by a participant. Having watched The Browning Version and Ian Holm’s shock when Millie suggests the gift is insincere, it’s suddenly very sad.

- TERENCE RATTIGAN

After The Dance by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV play 1992

All On Her Own by Terence Rattigan, Kenneth Branagh Company 2015

Flare Path, by Terence Rattigan, 2015 Tour, at Salisbury Playhouse

Harlequinade by Terence Rattigan, Kenneth Branagh Company 2015

Ross by Terence Rattigan, Chichester Festival Theatre 2016

Separate Tables by Terence Rattigan, Salisbury Playhouse 2014

Separate Tables, by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV version 1970

Separate Tables by Terence Rattigan (Table Number 7, Summer 1954) Bath 2024

Summer 1954 by Terence Rattigan (Table Number 7 / The Browning Version), Bath 2024

While The Sun Shines by Terence Rattigan, Bath, 2016

French Without Tears, by Terence Rattigan, English Touring Theatre 2016

French Without Tears, by Terence Rattigan, BBC Play of The Month 1976

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan (FILM VERSION)

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV Play, 1994

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, Chichester Minerva, 2019

The Deep Blue Sea, by Terence Rattigan, National 2016, NT Live 2020

The Deep Blue Sea, by Terence Rattigan, Bath Ustinov 2024

The Winslow Boy, by Terence Rattigan, BBC Play of The Month, 1977

The Browning Version, by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV play 1985

The Browning Version by Terence Rattigan (as Summer 1954), Bath 2024

JUDI DENCH

Peter and Alice (Grandage Company)

The Winter’s Tale (Branagh company)

Philomena (film)

The Joy of Six (film short)

Jane Eyre (film)

Belfast (film)

IAN HOLM

The Bofors Gun (film)

Leave a comment