By Sanaz Toosi

Directed by Diyan Zora

Set & Costume by Anisha Fields

The Royal Shakespeare Company

The Other Place

Stratford-Upon-Avon (until 1st June)

The production then transfers to the Kiln Theatre in London 5-29 June

Saturday 18th May 2024

CAST

Nadia Albina – Marjan, the teacher

Sara Hazemi- Goli

Lanna Jaffrey- Roya

Nojan Khazai- Omid

Serena Manteghi – Elham

The RSC’s studio theatre, The Other Place, had virtually fallen into disuse, but this is a step towards putting on productions there regularly again. It’s years since we were last there though we’ve often walked past it. It’s just a few hundred yards away from the main building. It has a superb coffee shop, seating areas with books and old RSC programmes, and the theatre itself must be double the capacity of Bath’s Ustinov Studio, which has been making a high reputation for itself. There is enormous potential for plays on a smaller scale than the Royal Shakespeare Theatre or The Swan.

The play won The Pullitzer Prize for Drama in 2022, and this is the European Premiere. Appropriately, we are seeing it on Omar Khayyam’s birthday. There are extracts from Farsi poets printed in the programme, though not from the best-known of them all. Farsi is the language of Iran, also known as Persian. I note that restaurants and recipes in the UK and USA like the word ‘Persian’ rather than Farsi or Iranian, but that’s the emigrant population.

We go with excitement and trepidation. My pseudonymous ELT comedy novel Home Affairs (LINKED) follows Iranian students in England in 1982 who were stranded by the revolution. I taught Iranians throughout the 1970s. We started to get requests for ‘original colour illustrated’ copies of our textbooks from Iran, because the version pirated by the government had eradicated the illustrations, and songs, and was black and white. We were invited to go there twice, and while I always wanted to see the country, I really can’t promote pirate copies of my books on which neither I nor OUP have ever been paid a penny. Then Karen corresponded with Iranian female students who sent her beautiful calendars (with traditional paintings of women in diaphanous clothing). Every time the news about Iran comes on we think of those fashionable, bright, friendly Iranian girls from the 1970s. What happened to them? Are their daughters and granddaughters forced into submission by these blood-stained old men in a theocracy?

I have no illusions about the Shah’s regime either. We placed three Iranians in a beginner class in the mid 70s. Two came separately to ask to be moved. I found an advanced level Iranian to translate. The third Iranian, a middle-aged woman, was the wife of a notorious secret police chief under the Shah. They did not want to be anywhere near her, for fear of offending by (e.g.) getting something right in a lesson which she got wrong. I shifted them. I soon saw their point. She was both thick and aggressive. We had to tell her that she could not slap younger students. By the time of the revolution, the area around the three main language schools was covered with Farsi graffiti, and it proved impossible to eradicate ‘Fuck the Shah’ in English on a wall at a prominent junction. However, Iran defines jumping out of the frying pan into the fire.

It is increasingly easy to see Iran as a walled island, a rogue state, a vicious theocratic dictatorship. However, an Iranian we worked with travelled back and forth regularly and until quite recently, she said it was easy to do so.

BUT to our great surprise, the play has absolutely nothing to say on the Iranian Islamic revolution, the position of women in Iran today, the rule of the Ayatollahs. The writer is Iranian-American, and the themes of cultural identity, the negatives for some people of the spread of English, the loss even of your name, could apply to many hyphenated Americans. The play could have been set in Turkey, Egypt, South Korea, The Philippines or anywhere else with a significant diaspora. The only note (and you’d have to know) is that Omid’s family travelled to the USA in 1980. In Bournemouth, Iranians bought every house in a cul-de-sac in 1980 (my co-author lived right by it) and for a couple of years had security guards parked in a car at the end of the street, in fear of the Ayatollah’s revenge squads.

I’m going to spend time on the EFL background.

My trepidation is that there are very few realistic portrayals of the language used in an ELT classroom, and Americans get it wrong more often than the British. I trust few to do it! The issue is that Americans assumed learners were ESL (English as a Second Language) and either immigrants or would-be immigrants. The British were used to EFL (English as a Foreign Language). An American editor asked me why there was no chapter on obtaining a Social Security number. I patiently pointed out that the largest market was Japan, and the learners there would have no intention of emigrating to the USA.

The class. Four students. This is not unusual for small private language schools. They are studying for the US TOEFL test which is needed for education, entry, visas etc. The range of abilities is not realistic. Roya is a near beginner, Goli is low intermediate, Elham has taken the test several times before, Omid is near native speaker level. It would be a really, really crap school to have this range of levels. In EFL, the larger the school the better. At Anglo-Continental, where I was Head of the Elementary Department 1975-80, I formed six classes at least a month. I separated one month courses from longer courses. I could have three different ability levels within that (zero beginner, low elementary, high elementary). I often had a separate class for an intensive one month course for ‘Non Roman Alphabet’ Arabic and Farsi speakers.

The students do not have any text books (highly unusual), but do listen to CDs of dialogue in American English. These are hilariously stilted, but are actually a very good representation of many real American English listening tapes.

They play vocabulary games by throwing a ball (Window! Door! Table!) but honestly I can’t imagine anyone trying this with high intermediate or above students. However, it’s done twice and is a perfect vehicle for showing how competitive Elham is.

But those vermilion stackable classroom chairs! We had them. I’ve seen them in private language schools from Mexico to Japan.

The teacher, Marjan (Nadia Albina) insists on using English in class, never translation. She’s right, and this would be the prevalent approach for well-trained EFL teachers. She is hugely enthusiastic about English language teaching and mortified when she herself makes tiny mistakes. i’ve met her (or rather hundreds just like her). It is a brilliant portrayal by Nadia Albina (the one highly experienced RSC actor) so that she is fluent with a very light Iranian accent, which can slip at times. It’s especially good as her profile shows her as a speaker of English and Arabic (a different accent), not Farsi. The way she calls students ‘darling’ is slightly inappropriate, but would have been picked up in Marjan’s nine years in Manchester. She’d be proud of it.

Sanaz Toosi deals with Farsi language interference in English in a subtle and limited way. There are classic areas of difficulty for Farsi, and she doesn’t flog them, just slips in an example or two of each.

• Articles. Farsi speakers drop a, an, the.

Goli: I need mirror.

Marjan: You need a mirror.

• consonant clusters like SPR -, STR -. Farsi and Arabic speakers add semi vowels

So STRAIGHT becomes SuTuRaight.

It happens on stage (SuCuREW I think) and is corrected, but is not noted in the text.

• Present / Past and Past / Present Perfect causes confusion

Elham: I take … I taked …

Marjan: Took

Elham: … took the TOEFL.

Marjan: You have taken the TOEFL before?

Elham: I have taken the TOEFL five times.

• There is no he / she distinction

That happens just once on stage, and is corrected by Marjan. I can’t find it in the text.

• Pronunciation problems are TH- sounds and V and W distinction. She only does a couple of TH- pronounced as T, but there is a lot of classroom practice on V and W. Marjan gets ‘Veels on the bus’ wrong once.

• Added auxiliary verbs like do / be

Goli: You do like …

There is no mention of the problems of reading at speed in the Roman alphabet. I assume the older elementary level Roya would need help there.

I have the feeling that the director and cast improved the text on language interference. A major scene is when Goli brings in a song she likes. It’s supposed to be 2008, but only according to the back cover of the text. It’s never mentioned on stage. The text (which credits this RSC English premier) has her bringing in a Ricky Martin song. The others are worried about his accent. In the production, it has been changed to another Hispanic singer, Shakira. Ricky Martin peaked in the early 2000s and was more popular in the USA than the UK. Shakira is much better known in the UK and her peak is later, and I think 18 year old Goli would have chosen a female role model (just as girls buy Taylor Swift or Shania Twain). The argument in class (that Shakira has not an American or British accent) shows that Sanaz Toosi is up with current ELT thinking … The English As A Lingua Franca movement accepts that English now belongs to the world, not just to native speakers.

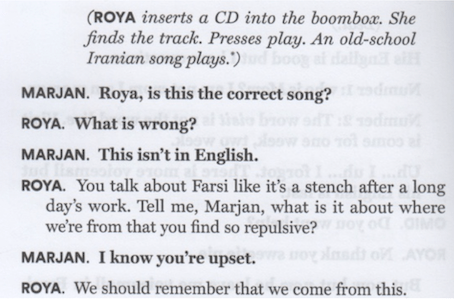

The characters use normal fluid British English when they’re speaking Farsi, and switch to accented mode when they are trying to speak English, which is compulsory in the class. They are penalised for speaking Farsi. This is shown in the play text by using bold print for English. The example is when they’ve been asked to present a song, and the older Roya, a grandmother, plays a song in Farsi:

This doesn’t work seamlessly, especially as over the six weeks of the course their English improves. There were a few points where we were unsure whether they were speaking fluent English (so Farsi) or Iranian English (So English).

They re-use the old joke (EFL students waiting patiently for a teacher with ‘Class Cancelled Today’ written on the board), but kind of lose it. Marjan had written ‘No class Wednesday” on the portable board the lesson before, then turned it round.

It is played in short scenes with blackouts, with characters taking it in turn to announce ‘Week one …’. It moves fast, played without a break in 95 minutes.

One review felt they weren’t ‘characters.’ We both disagree. we could identify them perfectly, but then we both spent years teaching.

Goli (Sara Hazemi) is eighteen, enthusiastic about English, sweet. Her very stance is diffident, head slightly bowed, respectful, but then she can suddenly be an excited teenager. She convinced us both absolutely. It also reminded us that eighteen in many cultures seems ‘younger’ than in the UK.

Elham (Serena Manteghi) is the stroppy and highly competitive one. She wants TOEFL so she can go to Australia and study Chemistry and earn money as a teaching assistant. Again, we’ve met the type. Highly accomplished in a subject in their own language, used to being a high achiever, but finding themselves forced to study English, simply to progress in studying Chemistry.

Marjan: English isn’t your enemy.

Elham: It is feeling like yes.

I know it well because our books sold particularly well in ‘non-English specialist departments’ in colleges and universities. It took me back to a teacher saying ‘I’ve just been teaching the thickies.’ The teacher was spending a month in Elementary, but usually taught Advanced level. I lost my temper and pointed out somewhat forcefully that the class contained a Mexican pilot, a Spanish sea captain, a Greek medical doctor and one of the top Swiss photographers as well as the German managing director of a large company. It was perhaps rude to say, ‘None of them are thick. They simply don’t speak English. You are clearly thicker than any of them.’ So Elham understandably resents learning English. It doesn’t happen to the British. As long as they can get a basic GCSE in one foreign language, they’re done (and that’s nothing like the level non-native speakers are expected to achieve in English.)

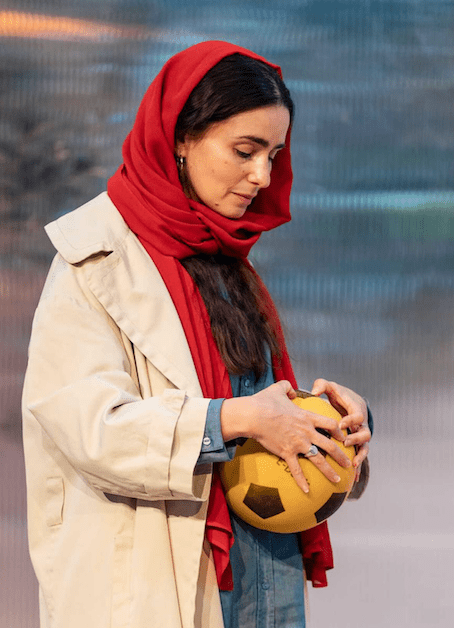

Roya (Lanna Jaffrey) is the oldest. A grandmother. Her English is the most limited (as is often the case with older students who find it harder). We notice her hair was fully covered … the three younger women just pay lip service to a headscarf. She has a permit to go to Canada, and wants to speak to her American granddaughter. She leaves Voicemail messages demonstrating her knowledge of numbers and colours. Her son is not replying. It is an extremely poignant performance, and Roya will leave the class before the end. Language and relatives abroad. We feel the slightest edge of her issue when speaking to our 6 year old grandson in America. We don’t see him for a year. It’s hard to maintain contact, and yet we don’t have a language barrier (he has more of a British accent too).

It comes up in names. Marjan was happy to be known as ‘Mary’ in Manchester. She suggests students adopt English names. I taught students who chose to do this of their own volition. We had to tell those Mexicans called Jesus that English people preferred the Spanish pronunciation and found the English one embarrassing. To Marjan’s surprise, the class resent it as a loss of identity. Roya is distraught that her granddaughter has a name she finds hard to pronounce, Claire. A colleague who had a Turkish wife was adamant that his sons had names that worked and were familiar and easy to say in both English and Turkish. Roya’s son hasn’t done that.

Omid (Nojan Khazai) is the conundrum. It becomes apparent that he speaks English more fluently and colloquially than Marjan. Why? No plot spoiler. Marjan watches romantic English movies with him ‘in office time.’ Elham is angry that Omid is the favourite, and that Marjan has taken a greater interest in him. Watch Nadia Albina’s silent hurt reaction when Omid announces his engagement. We wondered whether a lone male would be in a class with three women in Iran, but we don’t know.

To a degree, the play avoids the issues of Iran in the 2020s entirely. That’s a fault, or a missed opportunity in one way. In another, it’s a positive in that we see Iran not as an aggressive place with religious police in every doorway, but as “normal” or “just like us.” See the two girls above. In the end I liked that. I liked the theme of cultural identity. I believed in all the actors. The direction is fluid. The set looks real. I feel I’ve been in that room. The Other Place is a great venue too.

****

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

4 star

Catherine Love, The Stage ****

Michael Davies, What’s On Stage ****

Raphael Kohn, All That Dazzles ****

3 star

Domenic Cavendish, The Telegraph ***

Clare Brennan, The Observer ***

Suzi Feay, Financial Times ***

Mark Johnson Beyond The Curtain *** 1/2

2 star

Arifa Akbar, The Guardian **

LINKS ON THIS BLOG

DIYAN ZORA (Director)

Mom, How Did You Meet The Beatles? Chichester 2023

NADIA ALBINA

Macbeth National Theatre 2018

Macbeth, Globe 2016 (porter)

Hecuba, RSC 2015 (Cassandra)

Othello, RSC 2015 (Duke of Venice)

Othello, Wanamaker 2017 (Bianca)

Quiz,Chichester 2017

Leave a comment