By Dodie Smith

Directed by Emily Burns

Set & Costume by Frankie Bradshaw

Composer Nico Muhly

Performed 7 February to 27 March 2024

Lyttelton Theatre at The National Theatre

NT At Home, October 2025

CAST

Bessie Carter- Fenny

Pandora Colin – Edna

Bethan Cullinane – Cynthia

Lindsay Duncan – Dora

Kate Fahy – Aunt Belle

Tom Glenister- Hugh

Jo Herbert- Hilda

Billy Howle- Nicholas

Syakira Moeladi- Laurel

Amy Morgan – Margery

Celia Nelson – Nanny Patching

Dharmesh Patel- Kenneth

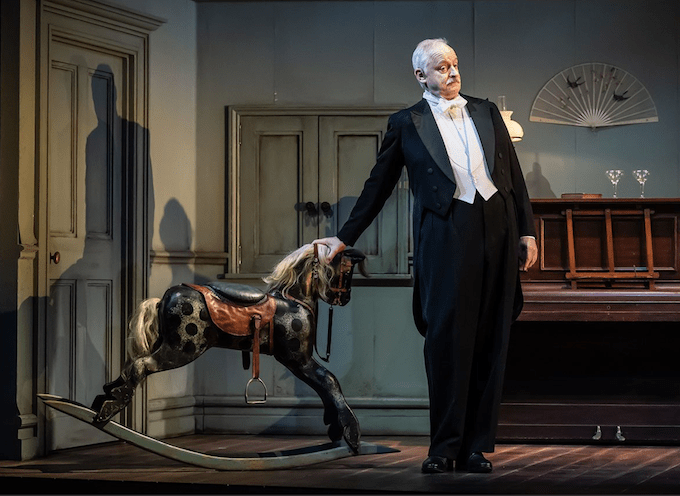

Malcolm Sinclair – Charles

Natalie Thomas – Gertrude the parlourmaid

+

three children:

Flouncy

Scrap

Bill

We chose this on NT At Home because we have seen three x 5 star Emily Burns directed plays in short order: Jack Absolute Flies Again, Love’s Labour’s Lost and Measure for Measure.

Dodie Smith (1896-1990) is Dodie ‘101 Dalmations‘ Smith, and in the 1930s she was a prominent playwright with Dear Octopus among others. Nowadays 1930s plays remind me of Karen’s old drama teacher’s shelf groaning With Best Plays of (1938) (1947) (1953) volumes. They were pre-Godot, pre-Anger.

Apart from spotted dogs, Dodie Smith had escaped my attention. She went to RADA in 1914, and as an actor toured for ten years. Her novel I Capture the Castle (1948) was voted #87 in a BBC poll of favourite novels, and has been a film, a BBC full cast audio play (on audio books) and even a Penguin ELT Graded Reader.

Dear Octopuswas a major West End hit twixt the Munich agreement and the start of the war. It ran for a year, September 1938 to September 1939, set off for the provinces in 1940 and went back to London for two more runs. John Gielgud starred as Nicholas. Wikipedia quotes the original Times review:

The fourth generation – or can we have lost count and this is the fifth? – remains unseen and unheard in the night nursery, but the other three are all present and correct. They are assembled to do honour to Charles and Dora’s golden wedding, and all the honours are done. In the first act the Randolphs explain themselves in the hall; in the second, laid in the nursery, they explain themselves in greater detail, recalling the past … and in the third act they drink the family toast, proposed by Mr Gielgud, and the lady companion is sought in marriage by the eldest son – Mr Gielgud again

Anonymous, The Times, September 1938

Emily Burns had directed Jack Absolute Flies Again, set just a couple of years later at the start of World War II. She must have immersed herself in the era.

It’s a domestic setting, three generations of the family gather for Dora and Charles’ Golden Wedding Anniversary. Even back in 1938, the critics mentioned that there was little or no plot. We noted that, and also that the dialogue was in places, to be kind, “of its time.” Was the appeal its traditional values as war loomed? The first night took place the day Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia to annexe Sudetenland. The audience was subdued, but lifted by the piece. It is said that hankies were out in Act 3 for most of its run.

In this production, the broadcast calling the Territorial Army to muster interrupts Act 1, and Chamberlains’ speech interrupts Act 3. Those can’t have been in the original text, and I assume are added now to give context, though I guess they might have been added a few days into the initial run. For the whole of that year everyone knew war was coming. Robert Harris’s novel Munich suggests that Chamberlain was advised by the chiefs of staff that they had insufficient military resources to act at that point, and that a year was needed to build planes and manufacture munitions. So ‘Peace in Our Time’ might have been a conscious lie (like ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction’ but in reverse).

It’s a family drama. They describe themselves as an ordinary family. Well, Charles the father retired at forty. They employ a cook, a chambermaid, a nanny and a lady’s companion. I suppose the line between ordinary and wealthy for the 1938 theatre audience was whether you could employ a butler, gardener and a chauffeur as well as the above.

A family tree would be extremely useful. Maybe they put one in the theatre programme. We only clarified the relationships over the course of the whole play. Maybe that was part of the enjoyment. Let’s try here.

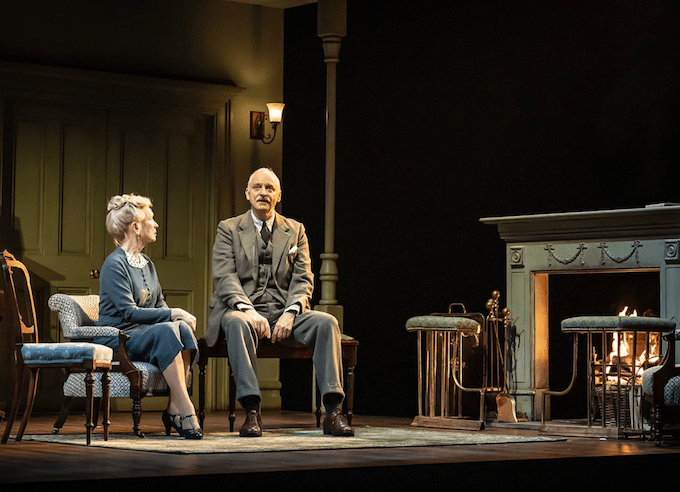

Charles (Malcolm Sinclair) and Dora Randolph (Lindsay Duncan) are having their Golden Wedding.

On the time scales, they are in their mid 70s. They can remember Charles’ mother as a strict Victorian. Dora mentions wearing a bustle as a girl, and that would make them born by the 1870s, courting in the 1890s. They had six children, four of whom are alive. Dora wants nothing more than having her family around her, but a running joke is that she constantly finds domestic tasks for every one of them.

Peter, presumably the oldest, was killed in World War One. His widow Edna (Pandora Colin) continues to visit family events, but is highly critical. She has central heating and electric light, not smoky coal fires and gas lamps. Edna is also a stirrer, particularly with Fenny, the lady’s companion.

Edna is the mother of Hugh (Tom Glenister) who is married to the starry eyed Laurel (Syakira Moeladi). Laurel is overwhelmed with the house … she grew up in a flat. They have a young baby, so Edna’s grandchild, Dora’s great-grandchild, who is never seen.

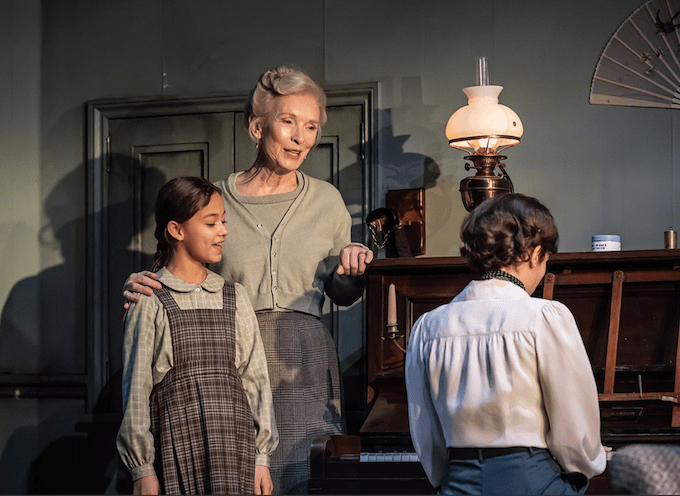

The Nanny is a lovely cameo by Celia Nelson. She was the nanny to all the 30 to 40 somethings and relishes having a baby and three children in the house. At the end, Dora offers to lend her to Laurel and Hugh for a year at her expense, and instructs Charles to give them an extra £1 a week towards her upkeep.

Then we have Cynthia (Bethan Cullinane), who has come home for the party after seven years in Paris, where she had a dark secret romance. Cynthia was a twin, and her twin sister Nora is dead, leaving a child named Scrap (or Gwen) who lives with her grandparents. Scrap is naturally drawn to her aunt. I had a friend whose mother was an identical twin and he said it was like having two mothers. Everyone tries to avoid mentioning her mother, but Scrap wants to know. One dramatic scene is when Dora and Scrap sing a song that the family knew as children, The Kerry Dance, and Cynthia, playing piano can’t take the memories.

Margery (Amy Morgan) is married to Kenneth (Dharmesh Patel). They have two children who appear, Bill and Flouncy. Margery is the butt of jokes about her weight. Kenneth is a cheerful flirt.

Hilda (Jo Herbert) is unmarried and has neurotic OCD, which irritates her siblings.

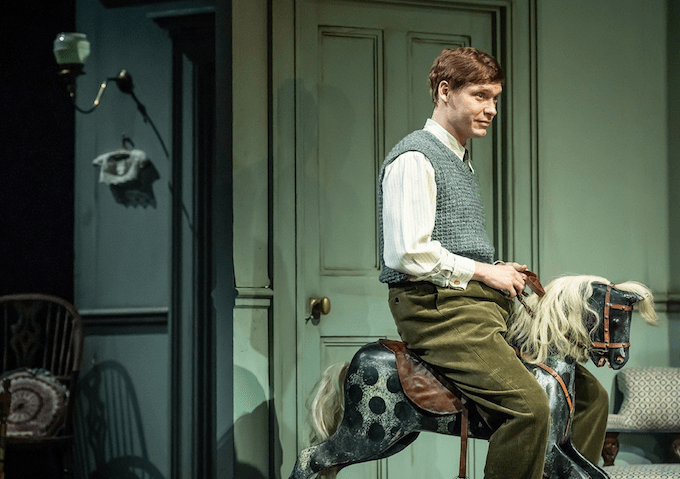

Nicholas (Billy Howle) is the brother, aged 35. He is the role John Gielgud took. He is utilised as an escort around London by his pushy sister-in-law, Edna. By the way, he is not the eldest son as The Times reviewer thought in 1938. Nicholas states that he was just too young for World War One (he would have been fifteen in 1918). His brother Peter was killed in it.

Fenny (Bessie Carter) is the companion for Dora. She has worked there for ten years since she was 19. For most of that time she has had a crush on Nicholas, and much of the theme is her being teased and hurt over it, by the sisters and by the unknowing Nicholas.

Aunt Belle (Kate Fahy) is the widow of Charles’ brother, William, who died thirty years earlier. She then married Elmer, an American who also died. She has had a torch for Charles for fifty years. She defines (if I may) the expression ‘mutton dressed up as lamb’ and Dora has cutting comments on that and her age.

Act one has everyone arriving in turn, so they can be introduced.

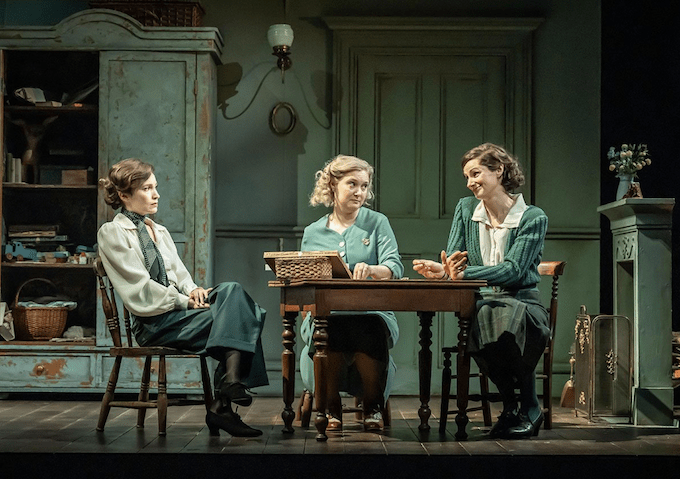

Act two takes place in the nursery. The three children take the first few minutes and do it extremely well. Gradually the adults gravitate there. Exploring memories is a central theme in the play, and the nursery focusses that. We have a scene with the three sisters which is one of the high points as we get the different personalities at full volume. The costumes say a lot and would have in 1938. Cynthia in tailored trousers, Margery in a loose frock, Hilda in sensible cardie and tweed skirt.

We also have Nicholas and some horseplay with Fenny, who is not sure how to react. Edna has revealed that they all know she has a crush on Nicholas.

Act 3 has more scenes in the nursery where characters have escaped from the dancing downstairs. Margery has asked Kenneth to flirt with Fenny to cheer her up. A brilliant piece of one high heel shoe walking from Bessie Carter.

Then Belle confronts Charles about how she’s fancied him for fifty years. Dora shrugs it off, as does Charles and there is a surprising dialogue on whether Charles is moving from atheism to agnosticis and whether he’ll reach her point of faith.

Then there’s the party the next day with the toast. Note Feeny towards the right in light blue. In the exapanse of the Lyttelton Theatre you might have missed her expressions as she listens. There, NT Live wins. The camera cuts and focusses on her in close up.

The title comes from that toast in the last Act and is intended as a positive:

We see a lot of the children, who are all very good, but there will be three juveniles cast for each role (that’s the law on the time they can spend on stage). They carry a lot of the humour, especially Bill and Flouncy, and are a difficult aspect of any production to carry off, especially for the adult cast who have to rehearse, then act, with all three. The children in the production photos are different to the ones in the streamed version.

The production is fluid, making full use of the elaborate revolve stage. Between the first scene, in the downstairs hall, and the second, in the nursery, the stage revolves to reveal a wordless breakfast scene. In Act 3, they can split scenes with a wordless return to the nursery. Then back to the hall, then the dining room, then the hall. You barely see the joins because the additions cover them.

It builds slowly. At first we were snotty about dialogue, and some does creak:

Hilda: Buck up, old dear!

Feeny: I’ve been making an ass of myself.

Nicholas describes the chicken farmer who wants to marry Fenny, the lady’s companion. So it’s classist (as was the world then):

Nicholas: The man’s a common little bounder.

However it IS a slow burner. We gradually got pulled in, then entranced. There is enough drama between the siblings, and there’s the rom-com Nicholas and Fenny element. It does promote the values of family, and also of being non-judgemental. Throughout Cynthia has feared Dora’s disapproval of her life style for years, but it turns out there is no disapproval. Just parental love.

I thought back to those 1938 comments that it had little plot. Three sisters, a sister-in-law, a woman who seems on the shelf but seeks romance, one bachelor brother, a domineering mother, a pleasant, benign but ineffectual father. Not much happens. That describes much of Jane Austen.

The cast are all first class … just look at the long list of links to other productions below. We’ve had Coward revivals, Rattigan revivals, I detect that a Maugham revival is just beginning. Maybe Dodie Smith will be next. The cast has twelve females and five males, if we include the children. Many theatres seek a 50 / 50 gender balance, and the sensible ones do it over the season (Chichester) rather than try and get it in every play (The Globe). Dodie Smith really helps the statistics.

One line seems fair:

Dora: It’s a good party. Nothing spectacular, but pleasant.

That sums up why it’s an almost universal ‘four star’ rating, but you do need a touch of ‘spectacular’ for five stars.

****

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

Unfairly dismissed as conservative and fusty, Thirties theatre dealt daringly with themes of identity and purpose. It’s ripe for reappraisal

Domenic Cavendish, The Telegraph February, 2024

The genius of Smith’s writing is that very little happens. Amid the family’s crossness and jokes and childish escapades, they’re all just figuring out how to be good to each other. Yet every missed opportunity and every gesture of kindness is made infinitely more poignant by the fleeting moment they stand in, with one war behind them and the next just ahead. Every moment becomes one to savour, for in the looming shadow of catastrophe, there doesn’t seem to be much more important than grasping at the precious little joys this chaotic family life can bring.

Kate Wyver, The Guardian, 15 February 2004

4 star

The Guardian ****

The Telegraph ****

Financial Times ****

The Independent ****

The Observer ****

The Stage ****

What’s On Stage ****

LINKS ON THIS BLOG

DODIE SMITH

I Capture The Castle (film) 2003

EMILY BURNS (DIRECTOR)

Measure for Measure, RSC 2025

Love’s Labour’s Lost, RSC 2024

Dear Octopus, National Theatre, 2024

Jack Absolute Flies again, National Theatre 2022 (Director)

Romeo & Juliet National Theatre 2021 streamed (Associate Director)

LINDSAY DUNCAN

Little Joe (film)

Birdman (film)

MALCOLM SINCLAIR

As You Like It, RSC 2023 (Orlando)

Pressure by David Haig, 2018 (Eisenhower)

Quartermaine’s Terms, Brighton 2013 (Eddie Loomis)

BETHAN CULLINANE

King Lear, RSC 2016

Cymbeline, RSC 2016 (Imogen)

Hamlet RSC 2016 (Guildenstern)

DHARMESH PATEL

Romeo & Juliet, Globe 2025 (Prince / Peter)

Much Ado About Nothing, Globe 2024

Love’s Labour’s Lost, Wanamaker 2018 (Berowne)

The Captive Queen, Wanamaker 2018

Titus Andronicus, RSC 2017

Julius Caesar, RSC 2017

Antony & Cleopatra, RSC 2017

Cymbeline, Wanamaker Playhouse 2015 (Soothsayer, Philario)

The Tempest, Wanamaker Playhouse 2015 (Ferdinand)

Two Gentlemen of Verona, Wanamaker Playhouse 2016 (Proteus)

JO HERBERT

The Southbury Child, Chichester 2022

The Country Wife, Minerva Chichester 2018

For Services Rendered, by Somerset Maugham, Chichester 2015 (Ethel)

Candida, by Shaw, Bath 2013

The Game of Love & Chance by Marivaux, Salisbury 2011 (Lisette)

AMY MORGAN

The Constant Wife, RSC 2025

Travesties, Menier 2016

The Beaux Stratagem, National Theatre (Cherry)

The Broken Heart by John Ford, Wanamaker Playhouse

An Ideal Husband, Chichester 2014

BILLY HOWLE

Life of Galileo, Young Vic 2017

PANDORA COLIN

8 Hotels, Chichester 2019

BESSIE CARTER

Bridgerton (TV series)

Leave a comment