By Helen Edmundson

Based on the novel by Jamila Gavin

Directed by Anna Ledwich

Designed by Simon Higlett

Composer & Sound designer Max Pappenheim

Choral music by Handel

Chichester Festival Theatre

Saturday 1st June1024, 14.30

CAST

Aled Gomer – Meshak Gardiner

Louisa Binder – Young Alexander Ashbrook / Aaron Dangerfield

Tom Hier- Dr Smith / Thomas Ledbury in 1750

Rebecca Hayes – Young Thomas Ledbury in 1742

Samuel Oatley- Otis Gardiner / Philip Gaddarn

Jo McInnes- Mrs Lynch

Jewelle Hutchinson – Miss Price in 1742 / Toby in 1750

Rhianna Dorris – Angel / Melissa Milcote

James Staddon – Theodore Claymore / George Friedrich Handel

Pandora Clifford – Lady Ashbrook / Mrs Hendry

Holly Freeman – Isobel Ashbrook

Milio McCarthy- Edward Ashbrook

Tallulah Grieve – Alice Ashbrook

Mrs Milcote- Debbie Korley

Harry Gostelow – Sir William Ashbrook

Will Attenbring – Alexander Ashbrook in 1750, aka ‘Mr Brooks

Coram Boy wasn’t a choice of a play I wanted to see, but down to me trusting that any major Chichester production would be worthwhile. The play dates from 2005 at the Olivier at the National Theatre, based on the novel from 2000. The novel won awards, but was always seen as a children’s novel.

It was acclaimed at the time, but was right off my radar. I knew nothing about it. We’re nearly twenty years on. Ripe for revival?

Chichester now doesn’t sell tickets for the back half of the auditorium or the balconies until the front half is nearly full. There are comments on line about it selling badly, and today we were all in the front half. The back and balconies were empty. Most unusual for a matinee. Online shows ‘good availability’ for the rest of the run. It doesn’t have instant appeal.

Much of the failure to get bums on seats is down to the choice of the flier / programme / poster picture. That stone cherub tells us nothing. It doesn’t evoke interest or the desire to find out more. It has nothing to do with the play either (OK, cherub / baby / angel?). I found it profoundly unappealing as an image, but, to repeat, I trust Chichester. Poor advertising here is the issue.

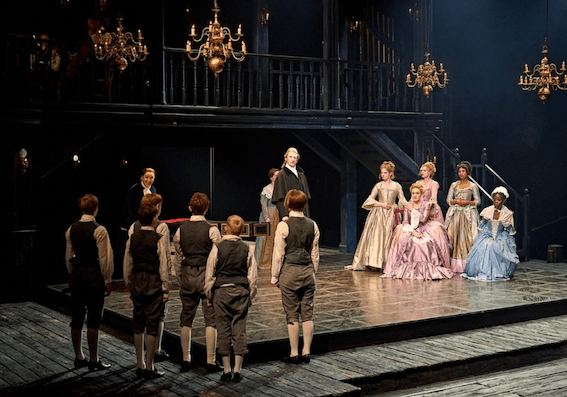

The stage has a sliding back and forth section which slides back to reveal the essential earth pits below. It’s mainly black, with organ pipes to show Gloucester Cathedral … the electronic keyboard is set at church organ and harpsichord, and actors mime the harpsichord which we can see being played above. I thought they had an issue with an unlit protruding black bottom step on a dark carpet while the audience was coming in. A lady fell flat on the floor tripping over it and within two minutes a man tripped at exactly the same place and just managed to stay upright. It needs a light, or at least an usher standing there with a torch. That’s a bad liability.

It is a difficult play. It has so many ultra-short scenes that the audience have no time to get engrossed in a scene before it moves on. There are THIRTY FIVE scenes in Act One alone. The direction is a triumph of stagecraft in moving a large cast, including children, off and on with such enormous pace. A number of the cast are women playing boys. This is not the normal gender blind casting though – they have to sing as choristers, and boys can’t do that when their voices break.

Meshak Gardiner is the somewhat retarded son of the evil Otis. He visits Gloucester cathedral where the choir is performing. Meshak looks up, and sees “An Angel.” The Angel will be played by the same actor as Melissa. Is it Melissa? No idea. I checked the text:

… a plaster sculpture with long glowing auburn hair, the bluest eyes and the kindest expression.

Well, here it’s Melissa with a white veil over her head. An aside: this breaks a scriptwriting rule, explained to me by Bob Spiers (Fawlty Towers, AbFab etc) who directed our first Grapevine series. Never predicate hair colour or eye colour unless it is absolutely essential to the plot. The writer might imagine a tall thin brunette, the casting director might find a short blonde who can play the part perfectly. The stage directions are over-written.

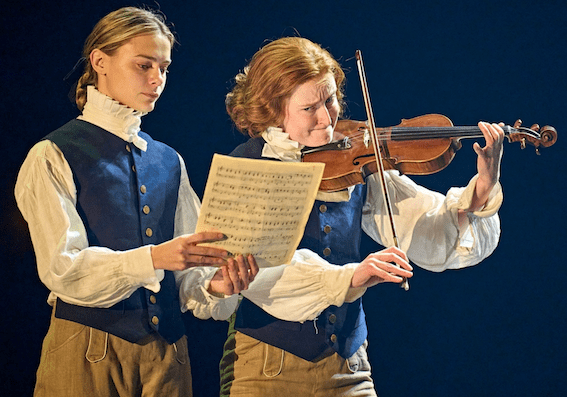

The story? It’s 1742. Gloucester. Alexander Ashbrook is the son of a wealthy local family. He wants to be a musician, and teams up with Thomas Ledbury, son of a carpenter, who also wants to be a musician. They are singing in Gloucester Cathedral’s choir school. Alexander discovers that Thomas doesn’t read music, but can play any tune he’s heard once.

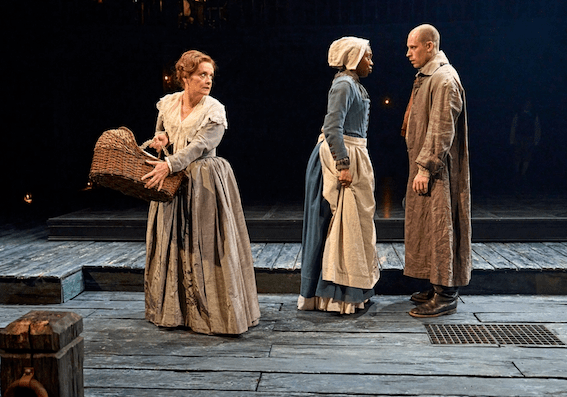

We discover that Otis Gardiner, a pantomime villain if ever you saw one, is in league with the Ashbrooks’ housekeeper, Mrs Lynch. He is pretending to work for the charitable Coram Foundation for “foundlings” (actually illegitimate babies). He is taking a baby from Miss Price. Having been paid by the mother to take them to safety in London, he disposes of the babies by burying them, sometimes alive.

At fifteen, Alexander knows his voice will soon break. When it does, he wants to continue studying music. Alexander’s dad, Sir William, refuses to let Alexander be a musician. Alexander goes home to visit, and takes his pal Thomas along. Thomas finds the assembled Ashbrooks intimidating.

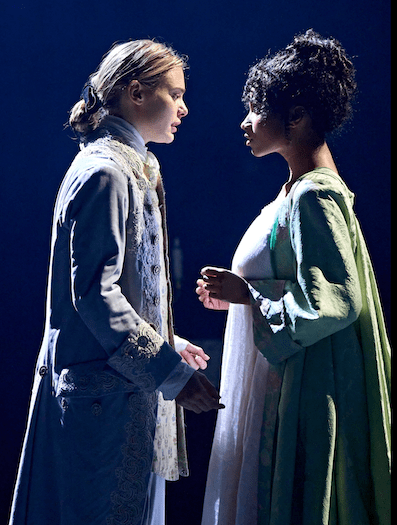

Melissa, a friend of the family is destined by her mum for romance with Alexander, what with him being Sir William’s heir. There is a decent Mills & Boone period where Alexander completely fails to notice the lovely Melissa. Then when Alexander sings for his father, his voice breaks. Puberty hits BANG! and he then instantly notices that Melissa is absolutely gorgeous.

Alexander and Melissa make love in the woods. Girls on top obviously as in all TV dramas. Then Alexander has to leave to seek a music career because he discovers that his and Melissa’s virginal is broken, they’ve lost their virginal … No sniggering at the back! A virginal is a simpler form of harpsichord. Virginal is what it’s called in the text. We assumed Sir William had smashed it. Perhaps Alexander did too. I bought the text. It was Meshak what done it.

Time passes (probably about nine months) and Melissa has a baby which is given to the dastardly Otis via Mrs Flynn. They ignore the stage direction about cutting the umbilical cord. Mrs Flynn tells Mrs Milcote, Melissa’s mum, that it is best to say the baby is dead. Melissa is told the baby was still born.

Meshak is dispensed by Otis to bury the baby. Then Meshak becomes the Egyptian pharoah’s daughter discovering Moses in the bullrushes. As he thought Melissa in the church was an Angel, he calls the baby Angel Child and runs away with it. Well, here. In the text he just sees the child as angel child.

Otis is caught when the baby graves are discovered and sentenced to be hanged. Very wisely, the director ignores another stage direction: MEN with dogs are digging up the ground by the lake. The dogs are eliminated. There is a stage rule: Never work with dogs or children. They are working with children. Dogs would be too much.

Act Two. 1750. London.

It’s shorter with a mere twenty-eight scenes.

Handel is a patron for the Coran foundlings. Two, Aaron and Toby, are about to leave the orphanage, being eight. They are Coram boys. Meshak had delivered Aaron safely to the Coram Foundation (children are named there). Meshak Gardiner works there as a handyman (gardener?) keeping his eye on Aaron and Toby.

Aaron is apprenticed to the musician Thomas Ledbury (YES! THE same one but an older actor).

Toby, being black, is sent off to be a livery servant to Philip Gaddarn, who has Toby dressed as an African prince (there is a long detailed description in the play text, at a length which will irritate a costume designer). 18th century paintings indicate this was a popular conceit for young black servants.

Gaddarn is a white slaver and terrifies Toby (this is the best speech in the whole play). He is acquiring young and virginal Coram girls (and boys) to be sent off to Turkish harems.

Alexander now poses as Mr Brooks, an assistant to Handel who is putting finishing touches to The Messiah.

Handel has a funny German accent, and as so many Germans do over the ages, especially during both the World Wars, can speak English well, but never learnt the word ‘No’ so says ‘Nein.’

The Coram boys choir is invited to sing at the Ashbrook Estate, invited by Lady Ashbrook. Sir William does not know.

Melissa and her mum have set up an orphanage what with guilt over the baby.

Aaron’s voice and look is strangely familiar. Guess what? Aaron (what with being played by the same actor as Alexander … Louisa Binder) is actually Melissa and Alexander’s eight year old son. He is big for his age. He was fifteen last time we saw him.

Mrs Milcote, Melissa’s mum, after eight years being blackmailed by Mrs Lynch, works it out.

Romance is rekindled.

The outraged family confront Mrs Lynch. She gives a rousing polemic speech about wealth. Yes, your sugar and your shirt cotton comes from slavery. I’m surprised they don’t all race over to Bristol and topple a statue of a slaveholder.

However, young Aaron has fled with Meshak. They seek him here. They seek him there.

There will be an attempt to rescue Aaron and Toby from Gaddarn who has captured them to sell as slaves, as villains do.

Gaddarn meets Mrs Lynch and removes his wig to reveal he is Otis Gardiner, who has changed names, but only a bit, from Gardiner to Gaddarn.

We see a “Famous Five” style fight.

Otis takes Aaron and Toby off to sea for a slave fate worse than death (I always suspected those Turkish sultans).

They are thrown overboard.

Meshak goes to rescue them and drowns (swimming about in green light).

There is a theatrical convention (or rather an RSC cliché) where dead characters walk solemnly through a doorway into the light. It happens here. Should it?

So will there be a happy ending?

That’ll do it.

The music … keyboard, violin, cello … and the singing is a wonder throughout the play. The programme lists Steve Dummer on clarinet. Do they mean ‘clavinet’?

It is inspiring to see such a young cast, and the kids playing the choristers, giving their all. Act two is better than Act one … four seats at least in our proximity were empty after the interval. Every actor is good. The direction was a phenomenal task, and it worked seamlessly.

It makes you think, about the fate of children, about 18th century wealth, about infant mortality, about slavery.

BUT there are too many conflicting stories without enough development time. There are massive swings from tragedy to corny romance to whodunit explanations. The one fight is not convincing. There isn’t much leavening of humour except for Thomas being bullied and singing a sea shanty. Having sped-read the script, the issues are intrinsic, and I’d place most of the issues with the story from the original novel. For example, if someone is going to escape or survive hanging, a degree of explanation or at least enigma over the hanging is requisite.

Then there’s visual casting. Melissa’s is Lady Ashbrook’s “cousin’s girl.” Play text:

ISOBEL … is shortly followed by another girl – older and extremely lovely with golden hair and piercing blue eyes. This is MELISSA.

I recall my quote from Bob Spiers on visuals. We have moved from a statue with auburn hair to golden hair, but both had piercing blue eyes. It made sense to have Rhianna Dorris (Melissa ) play the statue, thus leading to Meshak’s confusion. Rhianna Dorris is, as requested by the writer, extremely lovely (and excellent throughout). But there is an issue. They’re casting Melissa and her mother colour-blind. They are both Afro-Caribbean. That means they don’t look like the cousins of Lady Ashbrook. A theme of the play is slavery with Toby as the black son of a slave, and about to be sold as a slave. It’s 1742. Melissa and Mrs Milcote are aristocratic. It seems highly unlikely.

Later we get:

MRS MILCOTE: The boy – the Coram boy – he is so like you. He is so like Alexander.

“like” Alexander works, being the same actor. But “so like you” really doesn’t. No one is that colour blind.

Confusion is not helped by Miss Price. In the text she is a ‘very young lady.’ Lady? She is the one who hands her baby over to Otis at the start. She is played by Jewelle Hutchinson, who also plays Toby (and does so absolutely brilliantly) in Act Two. Toby has to be black, so Miss Price is black. That’s irrelevant to both the text and events. However, Miss Price was in a pale blue dress, similar to Mrs Milcote’s dress, so when Mrs Milcote is searching in the graves for the baby remains in near darkness, we weren’t sure whether it was Miss Price or Mrs Milcote. Tip: when it moves to Salford, change the dress colour!

On reading the text, much of the dialogue is trite. It betrays the origin as a children’s story. There’s a tribute to the actors and director, because it’s much triter in cold print than it ever seemed on stage. They made it work.

Yes, we were pleased we saw it. It’s full of movement and music. The cast are excellent and we liked the fact that there were so many new faces there, and the juveniles were superb. It goes on to Salford after Chichester too.

However, it IS confusing and the plot creaks quite severely at times. Overall?

***

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

I often disagree strongly with Arifa Akbar in The Guardian. She’s not afraid of bucking the consensus, but this time, I thought she made good points.

4 star

Domenic Cavendish, The Telegraph ****

2 star

Arifa Akbar, Guardian **

“hectic melodrama about the Georgian-era baby trade … Anna Ledwich’s production feels both ponderous and rushed, albeit with beautiful live music and choral song, but the cogs of the plot turn to such an extent that it overshadows all else. Even Handel pops up, his presence under-explained … Multiple scenarios are enacted on the spare set, designed by Simon Higlett, and there are swerves into dream-like expressionism, promisingly cutting through the naturalism. But these moments are rendered melodramatic as well with flashes of jagged light and sound“

The Guardian, Friday 31 May 2024

LINKS ON THIS BLOG

HELEN EDMUNDSON (writer)

Queen Anne, RSC 2015

SAMUEL OATLEY

King Lear, Bath 2013(Cornwall)