After The Dance

By Terence Rattigan

Directed by Stuart Burge

BBC Broadcast, “Performance” series, 5th December 1992

CAST:

Anton Rodgers – David Scott-Fowler

Gemma Jones – Joan Scott-Fowler

John Bird – John Reid

Imogen Stubbs – Helen Banner

Richard Lintern – Peter Scott-Fowler

Simon Beresford – Dr George Banner

Roberta Taylor- Julia Browne

Ben Chaplin – Cyril Carter

Georgina Hale- Moya Lexington

Celia Bannerman – Miss Potter

Geoffrey Beevers- Arthur Power

Malcolm Mudie- Williams (the butler)

Graham Seed – Lawrence Walters

After The Dance is Rattigan’s ‘Great Lost Play’ (or rather one of them), written in 1938. It opened in London in June 1939 and was a flop, lasting only 60 performances. It may not have been the best time to introduce the play’s depressing themes. Rattigan was understandably upset, and the play was excluded from his Collected Plays. It was an obscurity and this BBC production came fifty-three years after the original run, and seems the first major production in all that time. It was performed by the Oxford Stage Company ten years later in 2002, and then came Thea Sharrock’s National Theatre Production in 2010, starring Benedict Cumberbatch, Nancy Carroll and Adrian Scarborough. The play then should inspire all of us who are over seventy because in its seventy-second year it was hailed as a lost masterpiece and picked up four Olivier Awards.

Every few years the British theatre rediscovers Rattigan with an air of astonished surprise: this excellent production reminds us that we should simply accept him as one of the supreme dramatists of the 20th century.

Michael Billington, The Guardian, 9 June 2010

So this 1992 TV production was a major step in re-appraising the play. It is stricter than other BBC productions in sticking to the stage play. It takes place in one room, though we can see through to the next door dining room, but that is just like having an inner stage. There is a walk into the entrance hall. There is one exterior camera view of David on the balcony, but no outside location clips.

It opens with John Reid looking at newspapers on Chamberlain’s 1938 ‘Peace in Our time’ return from Munich. That sets it firmly, and also explains its 1939 West End demise. The date is fixed in the play. It’s about a ‘half-generation.’ They’re not Rattigan’s generation because he was born in 1911, so only seven years old when the Great War ended. The main characters in the play were just too young to be conscripted into that war, but came of age as it ended, so they are ten years, a half generation, older than Rattigan. They were the jazz age generation. The play makes the time-lines clear. The central characters, David and Joan Scott-Fowler have been married ‘fifteen years and seven months’ so since 1922. Their friends are all from that hedonistic period. They play the music of that period, especially Avalon (1920), fortunately an instrumental version rather than the Al Jolson original. Another is Dinah from 1925. This is an important point which is noted more than once. Music fixes you. (Hold on, pause in writing this to turn the record and play the other side of Abbey Road in the background).

We all know people who blossomed in a time period, and then decided to stay in it as did the characters here. They were the ‘bright young things of 1922’ but it is now 1938. My parents had friends in the 50s and 60s, and the woman still dressed in the high fashion of the early 1940s, bemoaning the lack of stockings with seams by 1965. I had an aunt in Canada who still dressed as ‘Miss 1941’ in 1966. I have friends proud of their Bob Dylan folk era Levi jackets. I know old hippies who dress as if it’s 1967. They’ve never stopped selling loon pants in Glastonbury town centre. In Poole, we have motor bike rallies on the Quay and they’re dressed as 1964 beach battle rockers (but very mellow now). At record fairs, I chat to people who think punk of 1977 is still the height of fashion. Then there are still Goths among us. I’m a little wary of those who think glam rock is still a sartorial guide.

Rattigan obviously disapproves of this half-generation older than him. Then he has Peter and Helen, just graduated in 1938, so a half-generation younger than him, a full generation younger than the jazz-agers. Joan Scott-Fowler is shocked to discover that Peter and Helen have known each other for two years but are still virgins. Times have changed. The 1938 young generation, post-Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the Depression, are very different. Helen was born in December 1918. So she is twenty. However for the Scott-Fowler’s wealthy and idle peer group life goes on much as it was in the early 1920s in a haze of alcohol. It’s not innocent fun either, a tale is told of Moya who was sitting next to the Lord Mayor at a banquet, needed a ‘fix’ and decided to use her hypodermic under the table. Inadvertently she missed and shot up the Lord Mayor instead, who passed out. As the film Babylon shows, hard drugs were a jazz age feature.

The plot. David Scott-Fowler (Anton Rodgers) is a wealthy historian. That is he has been writing a history of a Neapolitan king for five years. We don’t know whether he has actually published anything. I think he’s just rich. He lives in a Mayfair apartment with his wife, Joan (Gemma Jones) and a butler. Their friends pop in and out whenever. David is his younger cousin Peter’s guardian, and has employed him in a live-in secretarial role at £5 a week.

The opening scene: Richard Lintern as Peter, John Bird as John

Peter is played by Richard Lintern. David’s oldest friend, John (John Bird) is a permanent and extremely languid and idle house guest. John serves as the link character, and in the end, the judgemental one. With John Bird as John Reid quipping, and the Williams, the butler, being sent to ask him for bicarbonate of soda for the master, it looks as if we are in for a comedy.

Peter tells Joan that is hoping to marry Helen (Imogen Stubbs) who he met at Oxford. At the start he is typing up the notes he made with David at 5 a.m. Helen turns up with her brother George, a just graduated medical doctor. She wants him to examine David because he has a pain in the side which she puts down to his heavy drinking. She is told David won’t co-operate but she ploughs on regardless.

Richard Lintern as Peter and Simon Beresford as Dr George Banner / Imogen Stubbs as Helen Banner

Everyone in the first scene has a stiff morning drink except the three ‘Class of 1938’ ones. The older ones drink brandy, whisky or gin. When they discuss getting wine out for a party they agree that none of their circle will drink it, but best to put some out for show. Helen is desperate to persuade David to stop. No one else is bothered,

Helen as John Reid surmises, is desperately in love with David. Everyone has guessed it except Peter. It’s par for the course. That sort of schoolgirl crush happens in their circle, and it passes. Joan is not bothered.

Joan’s friend Julia turns up fresh from a flight from Le Touquet, and has consumed a bottle of brandy on the flight because they couldn’t bring it through customs. She has her current toy boy, the Estuary accented bit of rough, Cyril, with her. She forgets to introduce him. Joan comes out, but doesn’t remember meeting Cyril. She did, they had lunch the previous Thursday. These sort of people don’t matter to them, they come and go. Julia sinks more brandy, and Joan suggests they carry on their conversation while she is having her bath. Cyril tags along to the bathroom, but he can turn his face to the wall. It still looks like a comedy. Cyril and Julia are both very funny. As they leave:

Helen: Poor George! Were you shocked?

George: No, it was quite exciting. I’ve never met those sort of people before. I’ve only read about them.

David emerges. They all think David will take no notice of the doctor, but in the face of Helen’s insistence, he eventually submits to be examined.

Peter: I’m amazed if Joan or I had done what you’ve just done, we’d have had our heads bitten off.

Helen: David isn’t the ogre you think he is.

Joan and Julia come out, and her make up is now on. They recall a party where someone broke his leg. Very funny. Earlier they’d talked about someone who’d shot his girlfriend. Terribly amusing. then someone who tried to kill themself. Hilarious! Then there’s the Lord Mayor story. Julia sends Cyril to find a taxi, confused he bows deeply on exit,

Joan and Helen speak as Joan has her morning gin and cigarette. Helen explains that her brother is examining David. Ignoring the fact that Joan has been married to David for fifteen years, she starts to tell her about the drinking. She is monumentally insensitive and monumentally persistent.

Helen: If I’d known you minded, I wouldn’t have done it.

Joan: Oh, yes you would.

Helen: Alright, I would. I think someone ought to stop David drinking himself to death. Even if his own wife does stand by and do nothing.

Joan: You might have said she even encourages him. Oh, don’t let’s be bores, Helen, darling. It’s very good of you to take so much trouble. Especially over someone you hardly know.

Being a ‘bore’ is the ultimate sin in their circles. Helen picks up not a signal. Not a hint of ultra-polite sarcasm.

David comes out with Dr Banner. He is warned to go on the wagon or die. He does not tell Joan. Helen asks George if he’d convinced David it was the truth. Cirrhosis of the liver. George leaves, in one of the few ‘outside the room’ shots.

David: You don’t understand Helen. What I told him was the truth.

David comes out and goes straight for the Scotch. Helen knocks the glass out of his hand. He pours another and calls the butler to clear up the mess.

After an impassioned chat, Joan returns and asks David what the doctor said. ‘Wind. There’s nothing the matter with me,‘ he lies.

There is a time cut here, probably the Act break. In others in the Performance TV series these are marked by on-screen titles. Not here.

David dictates to Peter, while John Reid sits and irritates, bringing up the question of Helen’s infatuation. David is furious.. Julia comes back, there is a jokey conversation with David watching and glowering. It is a key moment:

Julia: You’ve been annoying my glamorous husband. I can see it in his face.

John: It’s his conscience that brought that blush to his cheeks, not I.

Julia: Now you be careful, John, I won’t have you annoying my little David. He means a lot to me.

John: About five thousand a year.

Julia: Seven, when the dividends are good.

John: Well, I hope you’re putting lot by, darling. You’re not as young as you used to be and you never know when some fresh-faced interloper mightn’t oust you.

Julia: Helen for instance.

John: Helen for instance.

Julia: I don’t worry about that. Any hanky-panky and I shall fly to my lawyers.

David is silently furious. The director here can’t resist some carefully lit filmic shots either. Who would?

£7000 in dividends? This why they never had to work. Money … Earlier we find that David earns £5 a week, £260 a year. He states that he would need £10 for married life. £500 a year. The average industrial wage was about £2.5s.0d. So in his humble role, David expected five times the national average to live. This shows how rich these people were.

There is a time cut, presumably an act break. David has taken her advice and is not drinking. Helen has been asked to read the completed manuscript of his history, and tells him it’s rubbish. There’s nothing worth keeping. He meekly agrees and throws five years work in the bin. She disparagingly tells him it’s not five years work at all, just a day here and there among the partying.

Helen: Every fault in the book comes from your own laziness.

Here comes the big love each other scene. They pour on the romantic music all over it, something you couldn’t do in the theatre.

They are preparing for a party … Joan has gone to Woolworths to buy 50 glasses at 3d each, plus tiny gifts for all, such as a rubber bath duck for John

John has guessed the truth … Helen is in love with David, and he is agreeing because he’s in love with her. He tells her:

John: You so glamourize and romanticize him that he hardly exists outside your imagination. A romantic little girl’s imagination.

Helen will take over David’s life, say that she wants to marry him (remember, they’re a prudish generation) and that she will inform Joan. He doesn’t volunteer to do it himself.

She does (Helen is truly vile in mixing supposed sweet sympathy with gloating victory) and Joan remains bright and accepting … on the surface. It is what one does. Then she breaks down when she speaks to John. The director will have been justifiably proud of those tricky mirror shots. Gemma Jones as Joan and John Bird as John Reid work perfectly in their roles.

It builds up to the party. There are more guests than a theatre production could afford (except for the National Theatre!) Moya is arguing over popular culture … The Marx Brothers and whether Mickey Mouse is superior to Donald Duck. She is also about to go ‘orf’ and fly over the Pole. Rattigan is having a dig here, I suspect. David does not look as if he is enjoying the company.

John is offered a job in Manchester to his horror. It’s from an old flame of Joan’s. Arthur runs a window cleaning company and turns up as the only one in an evening suit – a sartorial point, here. he’s from the ‘provinces’ so hasn’t latched on to their informality-though the women are all dressed formally.

Arthur’s conversation with John is the pointer to the future (and another reason the play failed to cheer Summer 1938 audiences). John lounges on the sofa. Arthur stands stiffly (ah, another mirror shot!)

John: I’m very happy to run away from the world.

Arthur: Yes. Until the world catches up by blowing you up in the next war!

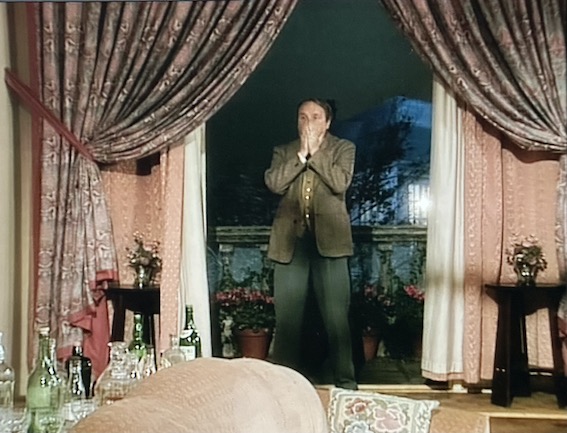

Everyone is drinking. Joan is heavily drunk. She opens the curtains to reveal a couple in deep embrace on the balcony. Reviews point out this was a particularly shocking scene at the National in 2010. It’s mild here.

Peter turns up to announce he’s leaving. He is distraught. David offers him money.

Peter: Keep your filthy money! I don’t need it! … I’m glad this has happened … You see I believe in a few things. Things you don’t believe in. I know I’m a “bore”. It’s the worst thing in the world, isn’t it … according to you, and John and Helen. I’m still a bore and I’m going to go on being a bore. if Helen would rather lead your sort of life, I wish her luck. I only thank God I found out about her in time.

David: Peter. Aren’t you being a little un-grown up about this?

Rattigan believed in a few things in 1938 too. That’s why he joined the RAF when the war started.

David recounts this to Helen, who blithely reacts ‘Poor David’ then after David says ‘Poor Peter.’ she responds ‘Come and kiss me.’ Joan walks in mid-snog.

After Helen has left, promising to come and talk to poor Joan the next day (Helen imagines she is a friend), there is a heart to heart conversation of regret that ‘it didn’t last a lifetime’. David kisses Joan’s hand.

Joan asks David to keep playing the piano, opens the curtains, goes to the balcony and closes them.

David keeps playing the piano and the others drift in. They begin to sing Avalon.The party goes on around David at the piano. John goes to look for her on the balcony … she’s not there.

It’s a powerful moment. I stood up to switch off the DVD player. Great ending! Hang on, what’s this? It hasn’t finished.

For us, it worked at John’s revelation at the party and the last Act was rather dull. Still, I suppose most want a resolution.

That would be another act break. It is six months later. Clothes are sombre. There is a new secretary, Miss Potter (Celia Bannerman) but with no typing to do she is knitting. John is packing to go to Manchester. He offers her novels, but she doesn’t read ‘novels.’

Horrible Helen has now firmly got her feet under the table, as they say. Her boundless insincerity has her say she hates the thought of John leaving. (Not). When David says how sorry he is to lose John, we get an anxious ;iYou didn’t try to put him off, did you?’ from Helen.

Peter turns up again interrupting a snog. Helen calls him ‘You little fool!’ and graciously suggests lunch the next day. She is showing how she has switched generations. Peter needs money, £20 or ten weeks wages in a factory, which David obliges him with. David suggests a job, but Peter talks of that looming future. That not very looming future in June 1939.

Julie turns up to discuss a party at Moya’s and starts on how about how she can’t bear to look at the balcony, and reminds him of another of their circle, Johnny Benson, who fell over a balustrade. She can’t have known anything about it.

David Shut up, Julie! Do you hear! Shut up!

David persuades Peter to meet Helen for lunch the next day.

It gets heavy. John says Peter needs Helen and she’d be better off with him. John says it’s nothing to him though, as they’re both just ‘bores.’

The butler arrives having found John’s rubber duck, the present from Joan (The poignant ‘Rosebud’ moment). He pockets it.

At last John said what no one admitted in their talk of poor Joan falling over a low balustrade. She killed herself.

David: You mustn’t miss your train.

John: I have no intention of doing tt. It’s got a restaurant car. I intend seeing Manchester for the first time through a mist of alcohol … God! Why am I doing this?

They say goodbye. The sad music swells. David goes in and closes the curtains. David decides to break it off with Helen. He tells Williams to take a letter to the restaurant and to pack, he will be going away tomorrow. The audience think, ‘At last.’ He phones Moya’s party and speaks to Peter. He asks him to promise to meet Helen for lunch the next day. He decides to go to the party and pours himself a stiff drink. Then he sits at the piano and plays Avalon with one finger while the credits role.

The fault of this production is that Helen’s passion for David and vice versa never seems remotely credible. We agreed that we had failed to work out her motive for saving him from the demon drink. General interfering? Florence Nightingale complex? He was a secret relative? It was a surprise when it was revealed as love.

They’re an unlikely pairing. He is old enough to be her father, and comes across as a grumpy accountant or bank manager. Helen is one of a line of unlikeable Rattigan portrayals of women. Diana in French Without Tears, Anne in Separate Tables, Millie in The Browning Version. Helen is toe-curlingly horrible (a compliment to Imogen Stubbs for making her so loathsome). She combines crassness, holier than thou attitudes, knowing best, dogged persistence, narcissism all with a strong streak of autistic. We thought Anton Rodgers acted the part of David well, but was simply miscast. He just doesn’t look right. We can imagine how Benedict Cumberbatch in that much-acclaimed 2010 production might have brought some dashing charisma to the part so that it made sense. It has been said that for actors to convince in love scenes they need one of three things. Genuine mutual physical attraction is the most important. Failing that, hating each other’s guts works too and often has produced dynamics. So does being best mates and having a good laugh about it (that tends to also happen one is heterosexual and the other homosexual). None of these appear to apply, and we both thought this production falls down because of it.

It is not a lost masterpiece for either of us, but then we never saw the 2010 cast.

- TERENCE RATTIGAN

After The Dance by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV play 1992

All On Her Own by Terence Rattigan, Kenneth Branagh Company 2015

Flare Path, by Terence Rattigan, 2015 Tour, at Salisbury Playhouse

Harlequinade by Terence Rattigan, Kenneth Branagh Company 2015

Ross by Terence Rattigan, Chichester Festival Theatre 2016

Separate Tables by Terence Rattigan, Salisbury Playhouse 2014

Separate Tables, by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV version 1970

Separate Tables by Terence Rattigan (Table Number 7, Summer 1954) Bath 2024

Summer 1954 by Terence Rattigan (Table Number 7 / The Browning Version), Bath 2024

While The Sun Shines by Terence Rattigan, Bath, 2016

French Without Tears, by Terence Rattigan, English Touring Theatre 2016

French Without Tears, by Terence Rattigan, BBC Play of The Month 1976

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan (FILM VERSION)

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV Play, 1994

The Deep Blue Sea by Terence Rattigan, Chichester Minerva, 2019

The Deep Blue Sea, by Terence Rattigan, National 2016, NT Live 2020

The Deep Blue Sea, by Terence Rattigan, Bath Ustinov 2024

The Winslow Boy, by Terence Rattigan, BBC Play of The Month, 1977

The Browning Version, by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV play 1985

The Browning Version by Terence Rattigan (as Summer 1954), Bath 2024

LINKS

IMOGEN STUBBS

The Browning Version, by Terence Rattigan, BBC TV play 1985

Communicating Doors by Alan Ayckbourn, Menier 2015

The Hypochondriac, Moliére / Richard Bean, Bath 2014

GEMMA JONES

Richard III, Old Vic, 2011 (Queen Margaret)

Rocketman (film)

Leave a comment